Forensic odontology 2026 – An introduction

Clinical relevance box

Collaboration between practicing dentists and forensic odontologists is often essential for the work of forensic odontologists. Increased insight in forensic odontology issues may facilitate this collaboration. Further, it may encourage particularly interested practicing colleagues to seek more information about forensic odontology issues or about post graduate education in this field.

Forensic odontology is a specialized discipline in dentistry. Forensic odontologists primarily work on assignment from authorities or closely related disciplines as forensic medicine. Examples of main tasks for forensic odontologists are personal identifications by means of the teeth, age assessments, and examination of evidence suspected to be of dental origin or objects/tissue with suspected dental involvement. This paper provides an appetizer in the form of an overview of the most important issues in forensic odontology which are covered in the present Nordic Theme issue.

Forensic odontology is a discipline operating with in depth analysis of odontological issues on assignment from judicial authorities and related disciplines, most often police and forensic pathologists. This paper introduces forensic odontology 2026 as reviewed in the present collaborative theme issue in which Nordic and international researchers present a contemporary overview of this special area of odontology

Main topics in forensic odontology

Personal identification

Personal identification is one of the primary tasks for the forensic odontologist (FO) [1]. Teeth and dental remains are among the most reliable and accessible means for establishing identity, as they are unique to each individual and can withstand extreme conditions such as fire, long lasting submersion in water or soil, traumatization and decomposition [2][3]. According to international guidelines forensic dental identification is recognized as one of the three primary identification methods, alongside DNA and fingerprints [4]. Forensic dental identification is based on a meticulous comparison of dental characteristics of a deceased with the dental records of a missing person. Post mortem (after death) detailed data on dental status, dental morphology, restorations, jaw related anatomical characteristics and complete radiographic records of teeth and jaws are used to match unidentified remains with corresponding data from missing persons [4][5]. The methods applied in forensic dental personal identification include digital techniques such as 3D intraoral scanning [6] and computed tomography [7].

Forensic odontology plays an essential role in the identification of victims following mass disasters [3]. Mass disasters - ranging from natural calamities like earthquakes and tsunamis to man-made catastrophes such as terrorist attacks or large-scale accidents, often result in severe destruction or disfigurement of the human body [8]. Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) refers to the standardized protocol developed by The International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) which is applied in many countries [4]. These guidelines include standardized procedures of all four phases of a DVI-operation, from scene examination to reconciliation to secure a uniform and safe way to identify individuals who have perished in disasters. The primary objective of DVI is to accurately establish the identities of the deceased, thereby providing closure to families, facilitating legal processes and enabling societies to be restored [4][9]. In a DVI-operation, forensic odontologists are typically responsible for gathering, transcribing, and comparing AM (ante mortem) - and PM (post mortem) dental data [10].

Figur 1

Figure 1. DVI team at work in the initial phase of the DVI process after the Asian tsunami December 2024. During the first weeks victims were gatherede and examined in protected temple areas.

Traditionally, forensic dental identification has relied heavily on the presence of dental restorations, matching those observed in the victim with existing dental records of missing individuals. Consequently, maintaining comprehensive dental records is fundamental for dental identification work. Dental record keeping in dental practices is an essential practice for both dental professionals and patients. It involves systematic documentation of a patient’s oral health history, diagnoses, treatment plans, procedures and other detailed information. Dental records serve several purposes, including the provision of high-quality care, ensuring legal protection for practitioners and patients, and maintaining continuity of care. How dental records are used for dental identification and what information forensic dentists need from the dental records to be able to do their work will be described in the article Dental records in the Nordic countries, which also covers the national regulations for dental records in all Nordic countries.

Age estimation

In victim identification, age estimation is essential in reconciling the identity of the deceased [1][4]. In young individuals the maturation status of teeth as well as eruption, and in older individuals’ degenerative changes like secondary dentine deposits can be evaluated. From a deceased, individual tooth specimen can be taken for age estimation purposes which is obviously not possible for the living. Age estimation methods by means of the teeth are covered in the articles Age estimation by means of the teeth and Minor or adult? Different approach in the Nordic countries vs Europe.

The methods for forensic age estimation in living people vary in the Nordic countries as well as Europe, and several countries lack legislation concerning forensic age estimation procedures [13]. Age estimation requested by immigrant authorities are most often on unaccompanied children (minor) and related to the question of being under the age of 18 [11].

When applying medical age estimation methods comprehensive knowledge of the normal timetable of development is required. In forensic medicine, the measurement of the height of the individual and development of bone or dentition are the most common methods applied [12].

In case the age of a living individual is unclear, non-medical age assessment methods, such as assessment of documentary evidence, psychosocial assessment, or an age-assessment interview, as well as medical methods of age estimation are used [13][14]. Other approaches to age estimation in the Nordic countries and in EU reviewed in the article Minor or adult? Different approach in the Nordic countries vs Europe.

Physical anthropology

Physical anthropology is the branch of anthropology concerned with the study of human biological and physiological characteristics and their development. Dental anthropology is a subdiscipline of physical anthropology that focuses on the use of teeth and jaws to resolve anthropological questions. The osteology of the skull and mandible, teeth, and adjacent tissues play an important role in identification of victims in mass disasters and criminal cases, unknown incomplete human remains and in human archaeological investigation. It may also add to the assessment of age, sex and stature [15][16].

Dental morphological anomalies, disturbances in the number of teeth (anodontia, polydontia or hyperdontia) and in eruption of teeth (impaction, ectopia) may be helpful clues in forensic dental profiling and forensic dental identification [17]. An overview of physical anthropology in forensic sciences is covered in the article Forensic anthropology“

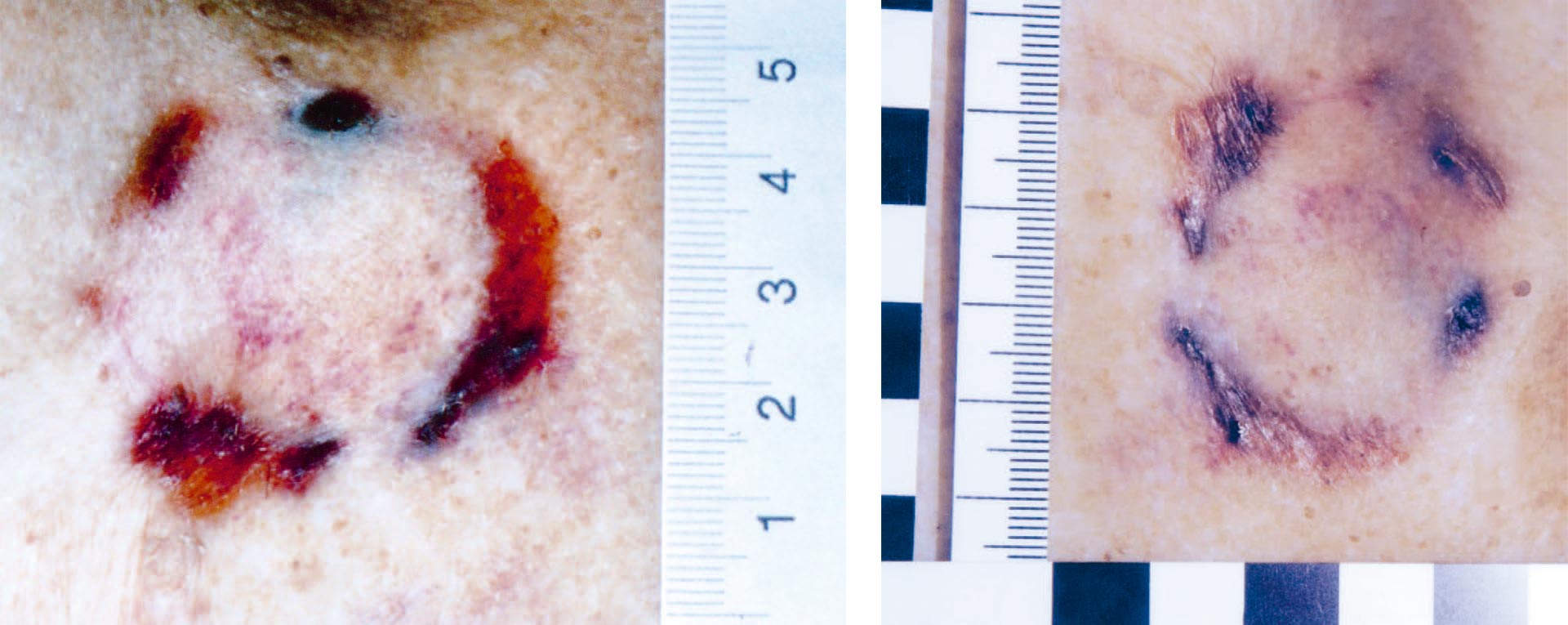

Analysis of bite traces

Bitemark analysis typically involves the examination of patterned injuries left on a victim or object at a crime scene, identification of those injuries, and comparison with dental impressions from a person of interest. Recent reports discuss the difficulties in generating reliable evidence from bite traces; scientific evidence is scarce [18]. The analysis of suspected bite traces is thus a controversial discipline in forensic odontology [19][20]. In the past several expert opinions on bite marks have unfortunately been presented on extremely dubious grounds, particularly in US where socalled expert testimonies were widely used [20] (figure 2).

Figur 2

Figure 2. Suspected bite mark in a homicide case. Forensic dental evaluation was requested.

The quality of bite marks can often be so poor that analysis should be avoided. Nordic forensic odontologists always have a very careful and sceptical approach to the analysis of bite traces.

Collecting DNA from bite marks (saliva swab) should be included whenever possible [21]. The challenges related to the analysis of bite traces are reviewed in the article Bite mark traces.

Dental aspects in domestic abuse

Domestic violence is defined as a recurring pattern of behaviors within an intimate relationship that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including acts of physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviors [22]. Domestic violence also includes other forms of abuse occurring in domestic settings such as abuse against children, elders or siblings [23].

The head, face and neck region are particularly vulnerable in cases of physical domestic violence and injuries within these locations have been considered markers of domestic violence with reports indicating up to 80% of the injury distribution in adult women [24] and between 50–75% in cases of child abuse [25] occur in these areas. The subject is covered in the article The role of the dental team in domestic abuse cases.

Dental professionals interact with a large number of patients daily, placing them in a unique position to observe signs of abuse, early identify victims and provide essential support. Dental practitioners are also in a key position to document and report suspected abuse, and many countries have a mandatory reporting requirement for suspected violence [26]. Oral and maxillofacial injuries in cases of domestic violence range from contusions and soft tissue lacerations to knocked-out teeth and jaw fractures. These injuries are not only painful but can have long-term consequences for the victim’s health and well-being. Furthermore, signs of neglect, such as untreated dental decay or poor oral hygiene, can also be indicative of broader patterns of abuse or neglect and should be carefully documented [26].

Recognizing and documenting dental trauma related to domestic abuse is a vital component of the investigative process and criminal proceedings. Forensic odontology plays a crucial role in supporting the criminal justice system and the dental community by providing education for dental staff and expert analysis in cases involving physical assault, especially those related to domestic violence [27].

Special trends in contemporary forensic odontology

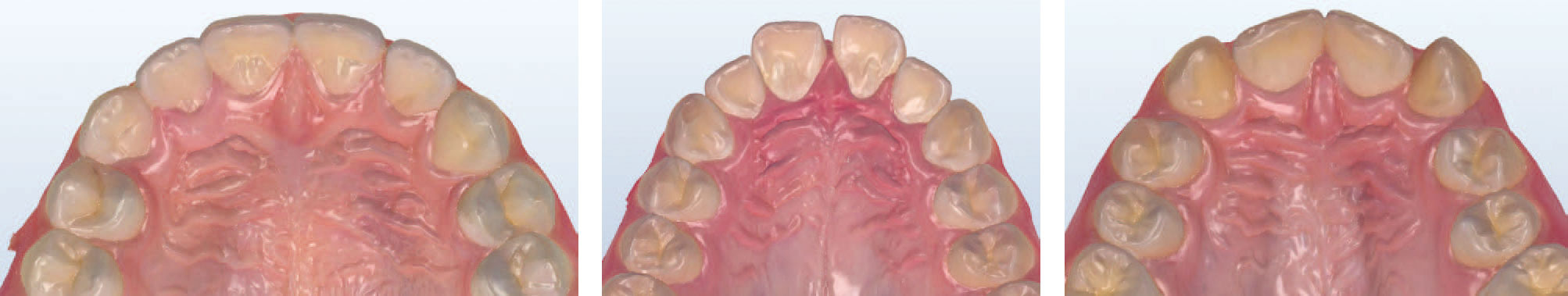

Rugae palatinae; the potential relevance in relation to personal identification

Analysis of palatinate rugae – irregular connective tissue ridges located on the hard palate – may be a valuable supplement to traditional dental identification that forensic odontologists should be aware of. The palatinate rugae maintain their distinct pattern throughout life and are believed to regenerate identical patterns even if damaged [28] (figure 3 a,b,c).

Figur 3

Figure 3. Different patterns of rugae palatini in 3 individual persons (a, b and c)

Studies have highlighted the uniqueness of palatinate rugae based on factors like their number, position, length, shape, direction, and density, recognizing them as reliable personal identifiers [29]. Situated centrally in the oral cavity and shielded by the cheeks, lips, tongue, teeth, and bones, the palatinate rugae are resilient against changes due to chemicals, temperature extremes, disease, or pre-mortem trauma, and often remain intact for up to a week post mortem [30].

As dental practices increasingly adopt digital scanning technologies (particularly in orthodontics and prosthodontics obtaining and sharing comprehensive digital replication of rugae and other dental features is becoming more approachable.

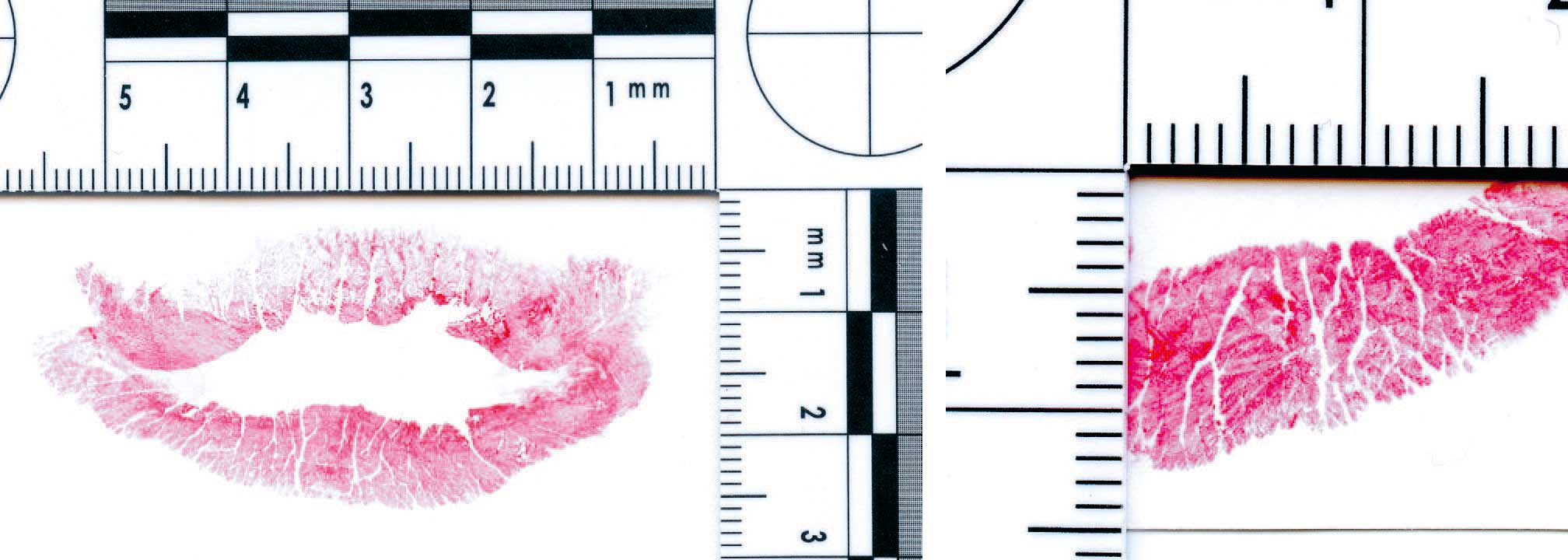

Cheiloscopy

Cheiloscopy or the analysis of lip prints, involves examining the distinct lines and fissures found in the types of grooves and wrinkles in the human lip’s transition zone, which is located between the outside skin or vermilion border and the interior oral labial mucosa. In forensic sciences, lip prints can be used to identify individuals and provide evidence in criminal investigations. Lip prints are often found at crime scenes on objects like cups, drinking glasses, cigarette butts, tissue papers and other objects. These prints can be collected from various surfaces and compared to known lip prints to identify the individual who left them behind. Lip prints can be analysed for characteristics such as shape, pattern, and ridge count, which may distinguish one individual from another [31] (figure 4).

Figur 4

Figure 4 a. Lip print, overview b. Lip print, details lower lip left

While cheiloscopy is a promising forensic tool, there are many limitations and challenges with its use. Environmental factors for lip prints can be affected by smudging, weather conditions, postmortem changes and improper collection techniques. Today there is no standardization when investigating lip prints like fingerprints and there is no universal database, which limits comparisons. In general lip prints are not yet recognized as conclusive forensic evidence limiting the legal acceptance of its use. Research is ongoing to establish more robust classification systems and integrate cheiloscopy with other biometric forensic techniques [32].

Introduction of 3D imaging in dental forensic identification

With the increasing use of intraoral 3D surface scanners in dentistry, e.g. as diagnostic tool in children and young adults prior to orthodontic treatment, many dental records contain digital 3D morphological data on teeth, palatal rugae and other intraoral features. Such data are extremely useful in identification cases, particularly when the deceased have had little dental work done leaving fewer details in relation to the use of common 2D data [33]. Ongoing research aims at developing reliable, user-friendly, quantitative scoring systems that allow forensic odontologists to quickly assess whether an AM and PM intraoral scan are deemed a likely match or an unlikely match. Such quantitative scoring systems will be very important for a quick sorting before identifying victims of major disasters [34] (figure 5).

Figur 5

Figure 5. 3D surface scans, occlusal views, of upper and lower jaws: tooth positions and detailed morphology of the individual teeth. In the related software the 3D models can be moved and viewed from all aspects.

5a, 5b: Upper and lower jaw of a living person

5c, 5d: Upper and lower jaw of a deceased. Note the detailed reproduction/documentation of the type and status of dental restorations.

Calculus analysis in forensic medicine and anthropology

Dental calculus trap micro-remains and molecules that are accidentally or intentionally inhaled/digested during daily activities [35]. As a result, dental calculus has been the subject of several studies of archaeological human remains. In recent years calculus as a source of forensic evidence has attracted interest [36]. It has e.g. been shown that a large variety of pharmaceutical and psychoactive drugs and degradation products are entrapped and preserved within calculus, among those heroin, cocaine and opium [37]. Some of such drugs may in criminal or abuse cases are not detectable in the body fluids at the time of autopsy but may have been a factor in the cause of death. Sensitive techniques for detecting drugs and their degradation products in calculus are not only applicable to modern forensic investigations but can also provide an overview of drugs and stimulants used in ancient time periods [37].

Conclusions

The main tasks for forensic odontologists are covered in this introductory paper which also provides a brief view at contemporary research areas in forensic odontology. For readers with evoked interest in forensic aspects of dentistry, a review of education in forensic odontology in the Nordic countries and in Europe is presented in the article. Forensic odontology education and training in the Nordic countries: pathways, programs, and prospects.

References

Taylor J, Kieser J, editors. Forensic Odontology: Principles and Practice. Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2016.

Sweet D. Interpol DVI best-practice standards – An overview. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;201:18–21.

Wood JD. Forensic dental identification in mass disasters: The current status. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2014;42:379–83.

Disaster Victim Identification Guide. 2023. INTERPOL. Lyon; 2023. https://www.interpol.int/How-we-work/Forensics/Disaster-Victim-Identification-DVI

Forrest A. Forensic odontology in DVI: Current practice and recent advances. Forensic Sci Res. 2019;4:316–30.

Perkins H, Hughes T, Forrest A, Higgins D. 3D dental records in Australian dental practice – a hidden gold mine for forensic identification. Aust J Forensic Sci. 2024;1–18.

Prokopowicz V, Borowska-Solonynko A. The current state of using post-mortem computed tomography for personal identification beyond odontology – A systematic literature review. Forensic Sci Int. 2025;367:112377.

Cattaneo C, De Angelis D, Grandi M. Mass Disasters. In: Schmitt A, Cunha E, Pinheiro J, editors. Forensic Anthropology and Medicine. Totowa: Humana Press; 2006. p. 431–43.

Hinchliffe J. Forensic odontology, part 2. Major disasters. Br Dent J. 2011;210:269–74.

Hill AJ, Hewson I, Lain R. The role of the forensic odontologist in disaster victim identification: Lessons for management. Forensic Sci Int. 2011;5:44–7.

Kenny MA, Loughry M. Addressing the limitations of age determination for unaccompanied minors: A way forward. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;92:15–21.

Schmeling A, Dettmeyer R, Rudolf E, Vieth V, Geserick G. Forensic age estimation: Methods, certainty, and the law. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:44–50.

European Asylum Support Office (EASO). Age assessment practices in EU+ countries: updated findings. EASO Practical Guide Series. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union. 2021.

Schumacher G, Schmeling A, Rudolph E. Medical age assessment of juvenile migrants—An analysis of age marker-based assessment criteria. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2018.

Jayakrishnan JM, Reddy J, Vinod Kumar RB. Role of forensic odontology and anthropology in the identification of human remains. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2021;25:543–7.

Ubelaker DH, Shamlou A, Kunkle A. Contributions of forensic anthropology to positive scientific identification: A critical review. Forensic Sci Res. 2019;4:45–50.

Richter S, Vidisdottir S. Dental profiling in forensic science and archaeology. Icelandic Dent J. 2022;40:32–43.

Sauerwein K, Butler JM, Reed C, et al. Bitemark analysis: A NIST scientific foundation review. NIST Ser NIST IR 8352. Gaithersburg; 2022.

Pretty IA, Sweet D. The scientific basis for human bitemark analyses – A critical review. Sci Justice. 2001;41:85–92.

Pretty IA, Sweet DJ. The judicial view of bitemarks within the United States criminal justice system. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2006;24:1–11.

Larsen LS. Bidmærkeanalyse. Tandlaegebladet. 2023;127:678–85.

World Health Organization. Responding to Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence Against Women: WHO Clinical and Policy Guidelines. Geneva; 2013.

Coulthard P, Yong SL, Adamson L, Warburton A, Worthington HV, Esposito M, et al. Domestic violence screening and intervention programmes for adults with dental or facial injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;8(12):CD004486.

Wong JYH, Choi AWM, Fong DYT, Wong JKS, Lau CL, Kam CW. Patterns, aetiology and risk factors of intimate partner violence-related injuries to head, neck and face in Chinese women. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):6.

Sibbal P, Friedman CS. Child abuse: Implications for the dental health professionals. J Can Dent Assoc. 1993;59:909–12.

Spiller LR. Orofacial manifestations of child maltreatment: A review. Dent Traumatol. 2024;40:10–7.

Hinchliffe J. Forensic odontology, part 5. Child abuse issues. Br Dent J. 2011;210:423–8.

Jain A, Chowdhary R. Palatal rugae and their role in forensic odontology. J Investig Clin Dent. 2014;5:171–8.

Chong JA, Mohamed AMFS, Pau A. Morphological patterns of the palatal rugae: A review. J Oral Biosci. 2020;62:249–59.

Poojya R, Shruthi CS, Rajashekar VM, Kaimal A. Palatal rugae patterns in edentulous cases – Are they a reliable forensic marker? Int J Biomed Sci. 2015;11:109–12.

Bhattacharjee R, Kar AK. Cheiloscopy: A crucial technique in forensics for personal identification and its admissibility in the Court of Justice. Morphologie. 2024;108:100701.

George Pallivathukal R, Kumar S, Joy Idiculla J, Kyaw Soe HH, Ke YY, Donald PM, et al. Evaluating digital photography for lip print recording: Compatibility with traditional classification systems. Cureus. 2024;16:e58238.

Forrest A. Forensic odontology in DVI: Current practice and recent advances. Forensic Sci Res. 2019;4:316–30.

Petersen AK, Bindslev DA, Forgie A, Villesen P, Larsen LS. Objective comparison of 3D dental scans in forensic odontology identification. Int J Legal Med. 2025. In print.

Larsen LS, Bindslev DA. Human calculus – et omfattende kartotek af informationer om livsstil og arvemasse. Aktuel Nord Odontol. 2021;46:35–48.

Forshaw R. Dental calculus – Oral health, forensic studies and archaeology: A review. Br Dent J. 2022;233:961–7.

Sørensen LK, Hasselstrøm JB, Larsen LS, Bindslev DA. Entrapment of drugs in dental calculus – Detection validation based on test results from post-mortem investigations. Forensic Sci Int. 2021;319:110647.

The article is peer reviewed.

Keywords: forensic odontology, forensic dentistry

The article is cited as: Bindslev DA, Sundwall AJ, Metsäniitty M, Kopperud SE, Vidisdóttir SR, Richter S. Forensic odontology 2026 – An introduction. Nor Tannlegeforen Tid. 2026; 136

Akseptert for publisering 14.05.2025. Artikkelen er fagfellevurdert.

Artikkelen siteres som:

Bindslev DA, Sundwall AJ, Metsäniitty M, Kopperud SE, Víðisdóttir SR, Richter S. Forensic odontology 2026 – An introduction. Nor Tannlegeforen Tid. year;vintage. doi:10.56373/69677966a17a9