Age estimation by means of teeth

Age estimation in children is applied in the identification process of a deceased child or when the age the child is questioned. In young individuals tooth development on radiographs as well as eruption are inspected, In adults several degenerative changes can be evaluated either in the laboratory or radiologically. From a deceased individual tooth specimens can be extracted for age estimation purposes which is obviously not possible for the living. Age estimation methods by means of the teeth are reviewed.

Clinical relevance box

Dental age estimation is used in clinical dentistry and orthodontics. In forensic odontology it is an important tool in assessing the age of asylum seekers and establish the identity of the deceased. Different methods for the living and deceased exist.

In forensic medicine, age assessment of an individual may be required, when the chronological age is unknown or cannot be verified. Besides victim identification, age assessment has become more frequent in establishing the age of an unaccompanied asylum seeking minor. Age assessment can also be requested by police authorities or in some countries by courts to clarify the legal age [1]. In pediatric and orthodontics dentistry dental development is used in diagnosis and treatment planning [2]. In forensic anthropology and archeology, age assessment is used to find the demography of the population[3]. Forensic age assessment may also be applied in competitive sports when an individual claims to be younger or older than chronological age. The sport competitor can have advantages by unfair physical superiority[1].

Different dental age estimation methods are applied for children, adolescents, and adults. The development of teeth is strongly genetically regulated, and the influence of environmental factors is small [4]. In adults, regressive changes in teeth must be used. Dental age assessment is considered reasonably reliable. Ionizing radiation is used, but the exposure is small, as well as the psychological burden of the method [5].

In the deceased this problem does not exist. In addition, teeth can be extracted for laboratory methods of age estimation, which would be unethical for the living. Eruption of the teeth can be applied as a clinical dental age estimation method during the active periods[6].

Asessment of tooth eruption in forensic age estimation

Tooth formation starts before birth at around 6 weeks of gestation for deciduous teeth and around 16 weeks for permanent teeth [7]. Different stages of tooth development define the dental age.

Tooth eruption can be assessed by clinical examination and/or by evaluation of dental radiographs. Eruption begins when the root starts to form and the emergence of teeth through the gingiva is a single event for each tooth. The stage of teeth eruption of an individual is compared with standard tables or atlas and then translated into a probable chronological age, however, the large variation in ages must be taken into account [8][9]. When analyzing the eruption of third molars panoramic radiographs are commonly used. However, in third molars visualizing the alveolar bone level, defining gingival or partial eruption, and recognizing full eruption may be difficult [9].

The timing and the path of emergence of permanent teeth may be affected by premature extraction of primary teeth and orthodontic treatment [10]. Impaction and pathological conditions may also affect the dental eruption [9].

In forensic age estimation, eruption may be used as a supplement to other dental age estimation methods [1]. The accuracy of dental age assessment will diminish without the use of imaging procedures [11]. The assessment of mandibular third molar eruption in panoramic radiographs cannot be relied upon for determining the age of majority [6].

Radiographic assessment of dental maturity in forensic age estimation

Previous studies have shown significant correlations between consecutive stages of dental development and chronological age. Panoramic radiographs are most often used to assess dental age [1] (figure 1).

Figure 1

Figure 1. Third molars are applied in forensic age estimation when all the other permanent teeth are mature.

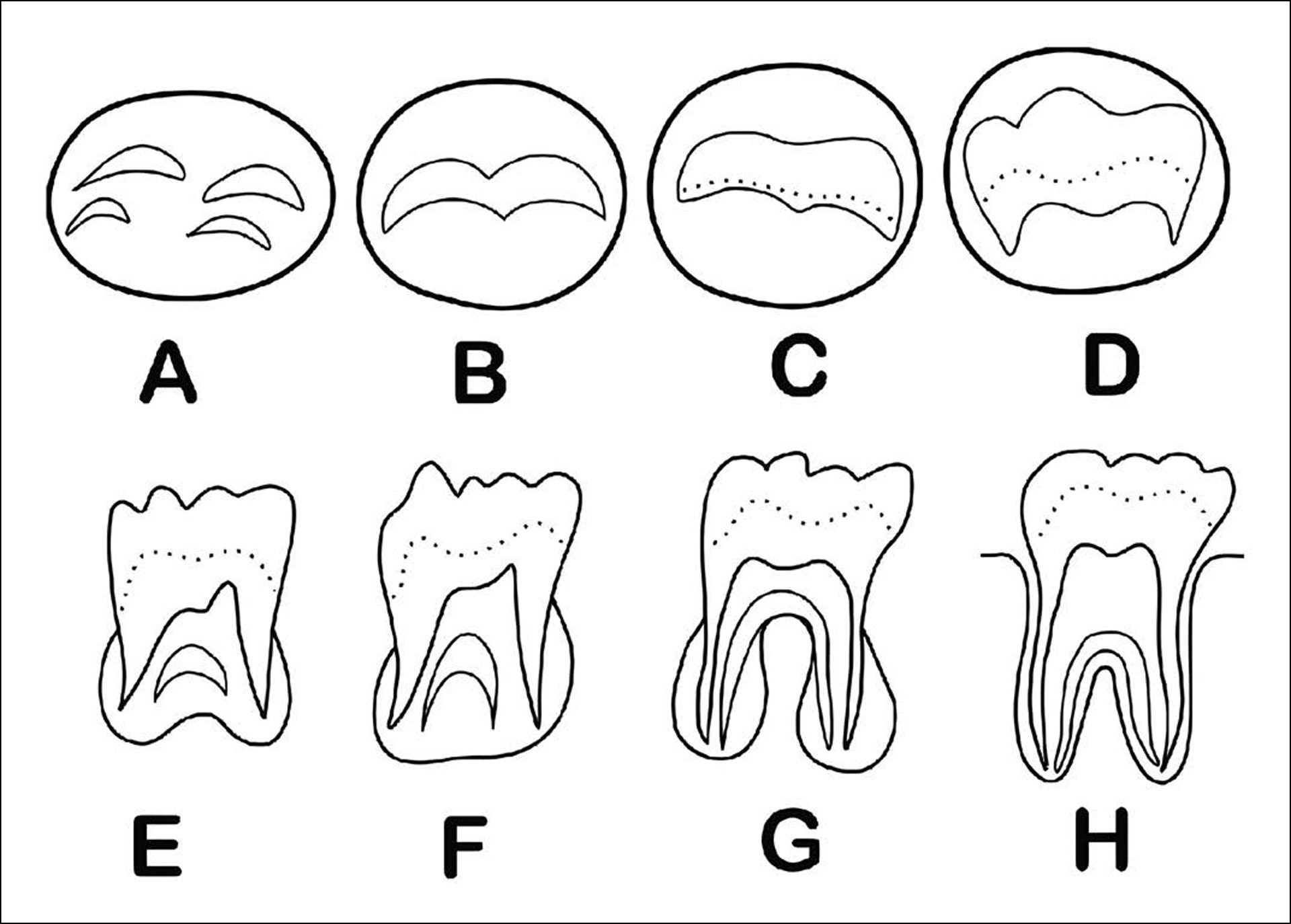

In the Demirjian et al. method [12] the development of the seven left mandibular permanent teeth (FDI 31 to 37) are staged. The contra-lateral tooth can be used when one or more index teeth are missing. The eight stages of development are named with letters from A to H, from the first appearance of calcified points to the closure of the apex (figure 2). Willems et al. [13] adapted Demirjian’s method using a large Belgian Caucasian reference sample and simplified the method so that calculation of maturity scores is avoided. The Willems method, when all the teeth 31-37 are mature, estimates the minimum age of 15.8 years for girls and 16.0 years for boys. This method seems to give best results.

Figure 2

Figure 2. Eight Demirjian stages for permanent multirooted teeth adapted after Demirjian et al. (1973).

The London Atlas, developed by AlQahtani et al. provides fast method for age estimation [9]. The method applies 13 stages for crown and root development and a free software program is available as well (https:/www.qmul.ac.uk/dentistry/atlas/). The third molar development is used in dental age estimation when all the other permanent teeth are mature. Several studies have been performed on development of third molars. The article “Minor or adult? A different approach in the Nordic countries vs. Europe”, in this thematic project cover the topic. Recent studies present new methods to decide on minor or adult status by applying transition analysis [14] or MRI segmentation of tooth tissue [15].

Examples of dental developmental staging techniques in age estimation are presented in table 1.

Laboratory methods for dental age estimation in deceased children and adults

Figure 3

Figure 3. Apical translucency on intact, extracted tooth.

Age assessment in deceased children is the same as used for living individuals described above. There rare cases are when the age of an infant under 1 year old needs to be assessed. From ground sections, made from still developing deciduous teeth, the daily enamel increments can be counted after the neonatal line, a distinctive line forming at the time of birth. This gives a more accurate estimate of age than development charts [17]. In adults’ teeth can be extracted, radiographed and sectioned. Gustafson [17]was one of the first to publish a method to assess age in adult teeth namely by grading attrition, periodontal recession, secondary dentine deposition, apical translucency, cementum apposition and root resorption. Gustafson studies were done on microscope slides of a few teeth – a very tedious and labourious method. Statistical shortcomings have exposed the method to criticism. Later studies have used a single factor or two to four of the factors [18][19][20][21] . Larger material and statistical calculations with the aid of computers have improved the results.

In single rooted teeth apical translucency and secondary dentine has been shown to be the two factors most strongly related to age. With age the apical translucency increases in length from the apex towards the crown (figure 3). Bang and Ramm developed a method to estimate age from the length of the apical translucency [18]. Using formula for intact teeth this is a simple and easy method to perform and is readily used in post mortem examinations. Lamendin’s method uses both apical translucency and periodontal recession [20]. Johanson scored all six factors using six scores, and with regression analysis the factors are evaluated according to their influence on age estimation [19]. Solheim studied different methods to quantify each of the age changes and selected the method which gave best result into a regression formula. This resulted in different methods of measurements for different types of teeth [21]. Other laboratory methods are radiocarbon dating (C-14) and amino acid racemization by measuring the conversion of amino acids from their L-form to the D-form.

Radiographic age assessment methods in adults

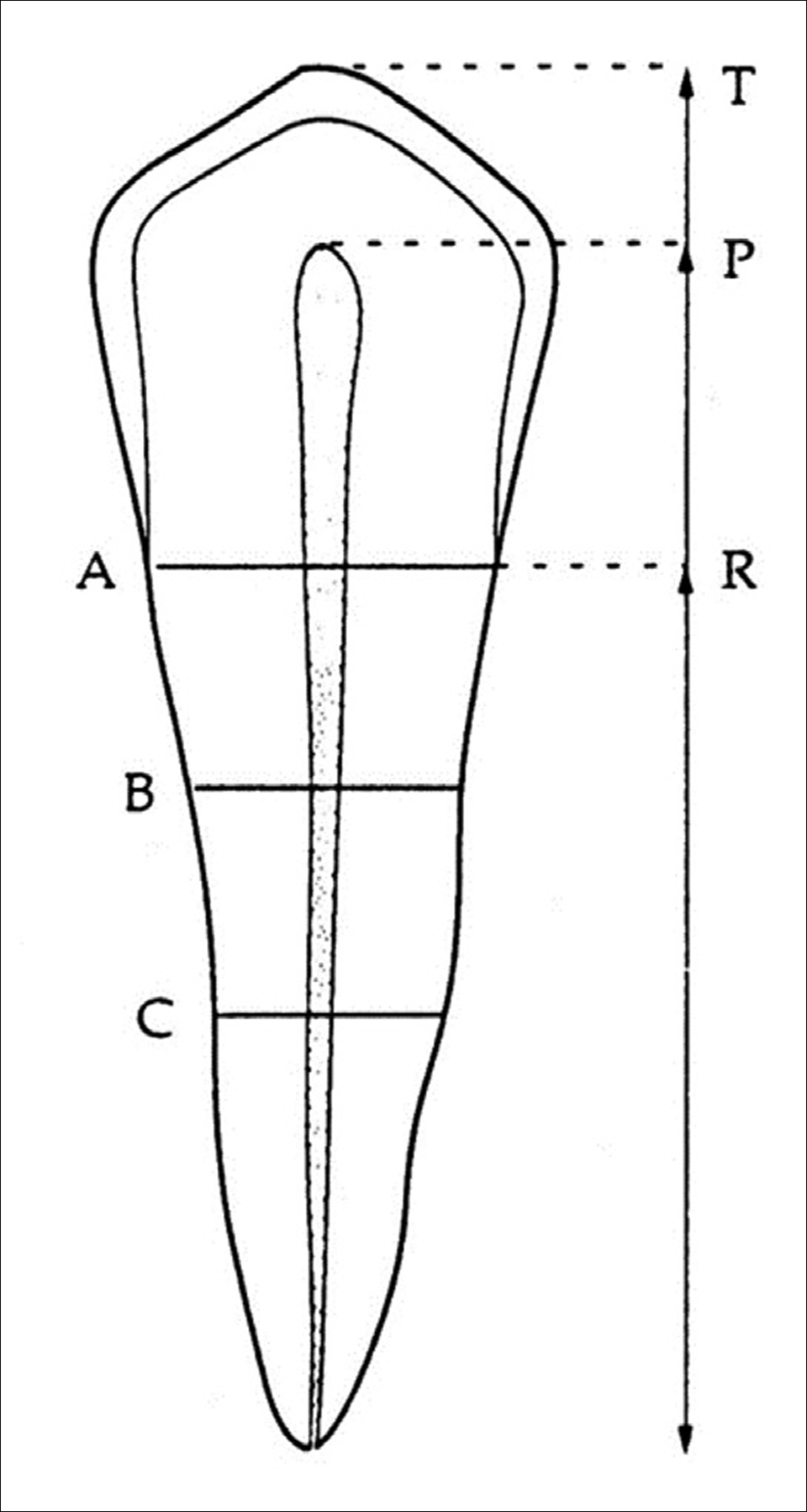

The pulp size is inversely related to age because of continuous deposit of secondary dentin and Kvaal et al. and Cameriere et al. measured the size of the pulp on radiographs in relation to age [3][22][23]. The methods are used worldwide and have become popular because they can be used in living people. “The Kvaal method” (figure 4) uses relative measurements on radiographs to avoid variations with different angles between the tooth and the film (sensor) [3]. Cameriere et al. also used dental radiographs and measured the area of the tooth and the pulp on canines both in the upper and the lower jaw [22][23]. The areas of the tooth and pulp is outlined, and the area are entered into a regression equation [24]. Because of the restriction inherited in the regression analysis, new equations have been developed which uses Bayesian calibrations – a statistical method which overcome many of the arguments towards regression [25][26].

Figure 4

Figure 4. Measurements on radiographs according to Kvaal et al. (1995).

With the introduction of computer tomography (CT) and cone beam CT (CBCT) attempts have been made to get more accurate measurement than can be obtained on a 2D dental radiograph [27]. Measurements have been on the size in the sagittal and axial plane according to the “Kvaal method” and also using volume measurement [28][29]. The measurements on CBCT either quantitative or volumetric are more accurate than using plain radiographs but also more time consuming and a higher x-rays dose is required. Machine learning procedures in dental age estimation are in its infancy and still require considerable time per tooth but may get more precise results.

Challenges in age estimation

Assessment of clinical eruption of teeth has limited use during inactive periods, and it is not as accurate as the mineralization status of the teeth [13]. In children the age assessment is performed by scoring the tooth development from 8–14 stages according to method. The stages are frequently described and illustrated with drawings and/or photos of single rooted and multirooted teeth. This grading is subjective, and many studies are based on study material containing age mimicry (skewed age distribution) and simple statistics. In addition, some of the stages have a wide age spans often depending on the number of stages see table 1.

When third molars are applied in forensic age assessment, large confidence intervals in development are problematic [30]. Earlier a population-specific reference sample was recommended, but the recent research rather recommends a reference data with uniform age distribution and a wide age range, and a Bayesian statistical approach [31]. The Bayesian approach takes into account correlation between the age indicators and the problem of missing indicators [32]. A recent study shows that when different nutritional and /or environmental circumstances are equal ethnic differences are negligible [33]. Malnutrition has little effect on dental development (4), however, some studies refer to advanced dental development in obese or overweight children [34] and in children with high-fat intake [35].

Ethical considerations

Dental age estimation plays a vital role in forensic legal cases, such as identifying migrants and disaster victims. However, it raises several ethical concerns that must be addressed. For the living ethical concern is informed consent. Obtaining consent for dental exams and imaging is crucial to respect autonomy and limit radiation exposure [36]. Bias and accuracy in age estimation are concerns, as many methods are based on specific populations and may not be universally applicable [37]. Errors in age estimation can significantly impact legal cases, asylum applications, criminal responsibility, and social services access [38]. Data protection and privacy are crucial in forensic investigations. Dental records must be securely stored and follow ethical guidelines like “General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)” [39]. Respecting the dignity of the deceased is essential in forensics. Ethical guidelines ensure respectful handling and ensuring that bodies are stored securely [1].

Future perspectives

The future of dental age estimation relies on advanced technologies, interdisciplinary collaboration, and ethical improvements.

Emerging technologies, such as AI and machine learning, can improve accuracy by analysing large datasets of dental images and reducing human error [40]. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) offers a non-ionizing, safe alternative, providing detailed images and mimic the risks of radiation [41].

Biochemical techniques like aspartic acid racemization and DNA methylation offer age estimation alternatives when traditional dental methods are unsuitable. These techniques allow good precision, when traditional dental methods are not applicable [42].

Standardizing guidelines and creating population-specific databases will enhance age estimation reliability across ethnic groups, require collaboration between forensic odontologists, anthropologists and legal professionals and is necessary to refine current methodologies [43].

Strengthening ethical regulations for dental age estimation is crucial. Forensic professionals must advocate for policies ensuring transparency, fairness, and human rights protection, especially for vulnerable groups like refugees and minors [36].

References

Schmeling A, Dettmeyer R, Rudolf E, Vieth V, Geserick G. Forensic Age Estimation. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:44–50. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0044

Celikoglu M, Erdem A, Dane A, Demirci T. Dental age assessment in orthodontic patients with and without skeletal malocclusions. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2011;14:58–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2011.01508.x

Kvaal SI, Kolltveit KM, Thomsen, IO, Solheim, T. Age estimation of adults from dental radiographs. Forensic Sci Int. 1995;74:175–85. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(95)01760-G

Elamin F, Liversidge HM. Malnutrition Has No Effect on the Timing of Human Tooth Formation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072274

European Commission. Joint Research Centre. Medical Age Assessment of Juvenile Migrants. Luxembourg: Publications Office; 2018.

Timme M, Viktorov J, Steffens L, Streeter A, Karch A, Schmeling A. Third molar eruption in dental panoramic radiographs as a feature for forensic age assessment – new reference data from a German population. Head Face Med. 2024;20:29. doi: 10.1186/s13005-024-00431-3

Hillson S. Dental Anthropology. Cambridge (England)/New York, NY: Cambridge University Press;1996.

AlQahtani SJ, Hector MP, Liversidge HM. Brief communication: The London atlas of human tooth development and eruption. American J Phys Anthropol. 2010;142:481–90. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21258

Kjær, I. Mechanism of human tooth eruption: review article including a new theory for future studies on the eruption process. Scientifica (Cairo). 2014:341905.doi: 10.1155/2014/341905

Hadler-Olsen S, Pirttiniemi PM, Kerosuo H, Sjögren A, Pesonen P, Julku J, et al. Does headgear treatment in young children affect the maxillary canine eruption path? Eur J Orthod. 2018;40:583–91. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjy013

Timme M, Steinacker JM, Schmeling A. Age estimation in competitive sports. Int J Legal Med. 2017;131;225–33. doi: 10.1007/s00414-016-1456-7

Demirjian A, Goldstein H, Tanner JM. A new system of dental age assessment. Hum Biol. 1973;45:211–27.

Willems G, Van Olmen A, Spiessens B, Carels C. Dental age estimation in Belgian children: Demirjian’s technique revisited. J Forensic Sci. 2001;46:893–95.

Arge S, Wenzel A, Holmstrup P, Jensen ND, Lynnerup N, Boldsen JL. Transition analysis applied to third molar development in a Danish population. Forensic Sci Int. 2020;308:110145. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110145

Bjørk MB, Bleka Ø, Kvaal SI, Sakinis T, Tuvnes FA, Eggesbø HB, et al. MRI segmentation of tooth tissue in age prediction of sub-adults - a new method for combining data from the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd molars. Int J Legal Med. 2024;138:939–49. doi: 10.1007/s00414-023-03149-0

Birch W, Dean MC. A method of calculating human deciduous crown formation times and of estimating the chronological ages of stressful events occurring during deciduous enamel formation. J Forensic Leg Med. 2014;22:127–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2013.12.002

Gustafson G. Age Determinations on Teeth. J Am Dent Ass. 1950;41:45-54.

Bang G, Ramm E. Determination of Age in Humans from Root Dentin Transparency. Acta Odontol Scand. 1970;28:3–35. doi: 10.3109/00016357009033130

Johanson G. Age determination from human teeth. Odontol Revy. 1970:1–126.

Lamendin H, Baccino E, Humbert JF, Tavernier JC, Nossintchouk RM, Zerilli A. A simple technique for age estimation in adult corpses: the two criteria dental method. J Forensic Sci. 1992;37;1373–79.

Solheim T. A new method for dental age estimation in adults. Forensic Sci Int. 1993;59:137–47. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(93)90152-z

Cameriere R, Ferrante L, Cingolani M. Variations in pulp/tooth area ratio as an indicator of age: a preliminary study. J Forensic Sci. 2004;49:317–19.

Cameriere R, Ferrante L, Belcastro MG, Bonfiglioli B, Rastelli E, Cingolani M. Age estimation by pulp/tooth ratio in canines by peri-apical X-rays. J Forensic Sci. 2007;52;166–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00336.x

de Araújo PSP, Pinto PHV, da Silva RHA. Age estimation in adults by canine teeth: a systematic review of the Cameriere method with meta-analysis on the reliability of the pulp/tooth area ratio. Int J Legal Med. 2024;138:451–65. doi: 10.1007/s00414-023-03110-1

Aykroyd RG, Lucy D, Pollard AM, Solheim T. Technical note: regression analysis in adult age estimation. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1997;104:259–65. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199710)104:2<259::AID-AJPA11>3.0.CO;2-Z

Cameriere R, Luca SD, Vázquez IS, Kiş HC, Pigolkin Y, Kumagai A, et al. A full Bayesian calibration model for assessing age in adults by means of pulp/tooth area ratio in periapical radiography. Int J Legal Med. 2021;135:677–85. doi: 10.1007/s00414-020-02438-2

Yang F, Jacobs R, Willems G. Dental age estimation through volume matching of teeth imaged by cone-beam CT. Forensic Sci Int. 2006;159(Suppl 1): S78-83. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.02.031

Bjørk MB, Kvaal SI. CT and MR imaging used in age estimation: a systematic review. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2018;36:14–25.

Merdietio Boedi R, Shepherd S, Oscandar F, Franco AJ, Mânica S. Machine learning assisted 5-part tooth segmentation method for CBCT-based dental age estimation in adults. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2024;42:22–9. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.11061543

Liversidge HM, Marsden PH. Estimating age and the likelihood of having attained 18 years of age using mandibular third molars. Br Dent J. 2010;209:E13. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.976

Liversidge HM, Peariasamy K, Folayan MO, Adeniyi AO, Ngom PI, Mikami Y et al. A radiographic study of the mandibular third molar root development in different ethnic groups. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2017;35:97–108.

Fieuws S, Willems G, Larsen-Tangmose S, Lynnerup N, Boldsen J, Thevissen P. Obtaining appropriate interval estimates for age when multiple indicators are used: evaluation of an ad-hoc procedure. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130:489–99. doi: 10.1007/s00414-015-1200-8

Thevissen P, Waltimo-Sirén J, Saarimaa HM, Lähdesmäki R, Evälahti M, Metsäniitty M. Comparing tooth development timing between ethnic groups, excluding nutritional and environmental influences. Int J Legal Med. 2024;138:2441-57. doi:10.1007/s00414-024-03279-z.

Hilgers KK, Akridge M, Scheetz JP, Kinane DE. Childhood obesity and dental development. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:18–22.

Jääsaari P, Tolvanen M, Niinikoski H, Karjalainen S. Advanced dental maturity of Finnish 6‐ to 12‐yr‐old children is associated with high energy intake. European J Oral Sciences. 2016;124:465–71. doi: 10.1111/eos.12292

Thevissen PW, Kvaal SI, Willems G. Ethics in age estimation of unaccompanied minors. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2012;30(Suppl 1):84–102.

Liversidge HM, Smith BH, Maber M. Bias and accuracy of age estimation using developing teeth in 946 children. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;143:545–54.

European Asylum Support Office. EASO, Annual Report 2017. 2018. https://www.euaa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EASO-Annual-General-Report-2017.pdf

Council of the European Union. General Data Protection Regulation GDPR. 2016. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/data-protection-regulation/

Vodanović M, Subašić M, Milošević DP, Galić I, Brkić H. Artificial intelligence in forensic medicine and forensic dentistry. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2023;41:30–41.

De Tobel J, Hillewig E, Bogaert S, Deblaere K, Verstraete K. Magnetic resonance imaging of third molars: developing a protocol suitable for forensic age estimation. Ann Hum Biol. 2017;44:130–9. doi: 10.1080/03014460.2016.1202321

Meissner C, Ritz-Timme S. Molecular pathology and age estimation. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;203:34–43. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.07.010

Espinoza-Silva PV, López-Lázaro S, Fonseca GM. Forensic odontology and dental age estimation research: a scoping review a decade after the NAS report on strengthening forensic science. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2023;19:224–35. doi: 10.1007/s12024-022-00499-w

Corresponding author: Mari Metsäniitty, Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. E-mail: mari.metsaniitty@thl.fi

Accepted for publication 13.05.2025. The article is peer reviewed.

Keywords: dental age, dental development, age estimation, forensic age estimation, forensic odontology

The article is cited as: Metsäniitty M, Víðisdóttir SR, Kvaal SI. Age estimation by means of teeth. Nor Tannlegeforen Tid. 2026. doi:10.56373/6932e44561553

Akseptert for publisering 13.05.2025. Artikkelen er fagfellevurdert.

Artikkelen siteres som:

Metsäniitty M.Víðisdóttir SR.Kvaal SI. Age estimation by means of teeth. Nor Tannlegeforen Tid. 2026;136:18-23. doi:10.56373/6932e44561553