Minor or adult? A different approach in the Nordic countries vs Europe

Around 1 out of 5, or 150 million children under the age of 5 worldwide are unregistered or lack a birth certificate. Unaccompanied minor migrants have many benefits, inaccessible to adults. It is evident that the age of migrants is one of the key variables that must be ascertained. Equally, it is important that juveniles are housed under safe conditions, including not with adults stating to be children.

In contrast to teeth, bone growth is dependent on nutrition and stimuli. Teeth and bone develop independently, consequently, it might be a good argument for using both dental and bone development in medical age estimation.

The Nordic countries use dental development to estimate the age by staging wisdom teeth from radiographs. All countries, but Norway, also estimate age based on skeletal maturity. In addition, Finland and Denmark use physical maturity criteria and Denmark sexual maturity. Various recognized scientific methods are used by the different countries.

All EU + countries, except Ireland, approve some form of medical age assessment. 21 use dental radiograph analysis and 16 dental observations. 23 countries use carpal (hand/wrist) radiographs, 14 collar bone radiographs and 2 knee MRI and 8 sexual maturity observation.

Headline

Medical age estimation attempts to ensure minors their benefits they have according to international law and prevent adults from taking rights that are reserved for children.

Unaccompanied minors are children under the age of 18 years [1], who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law is responsible for doing so.

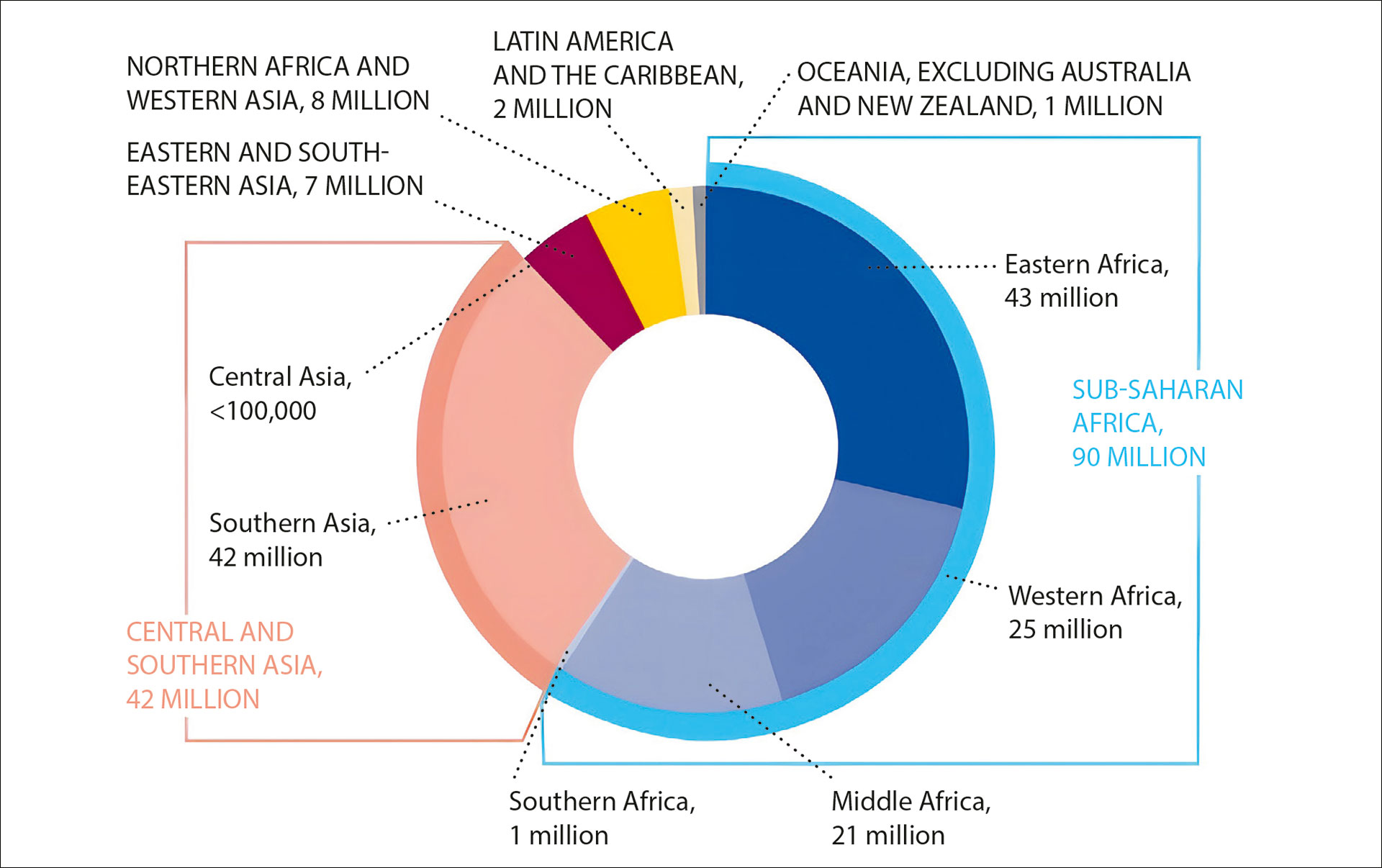

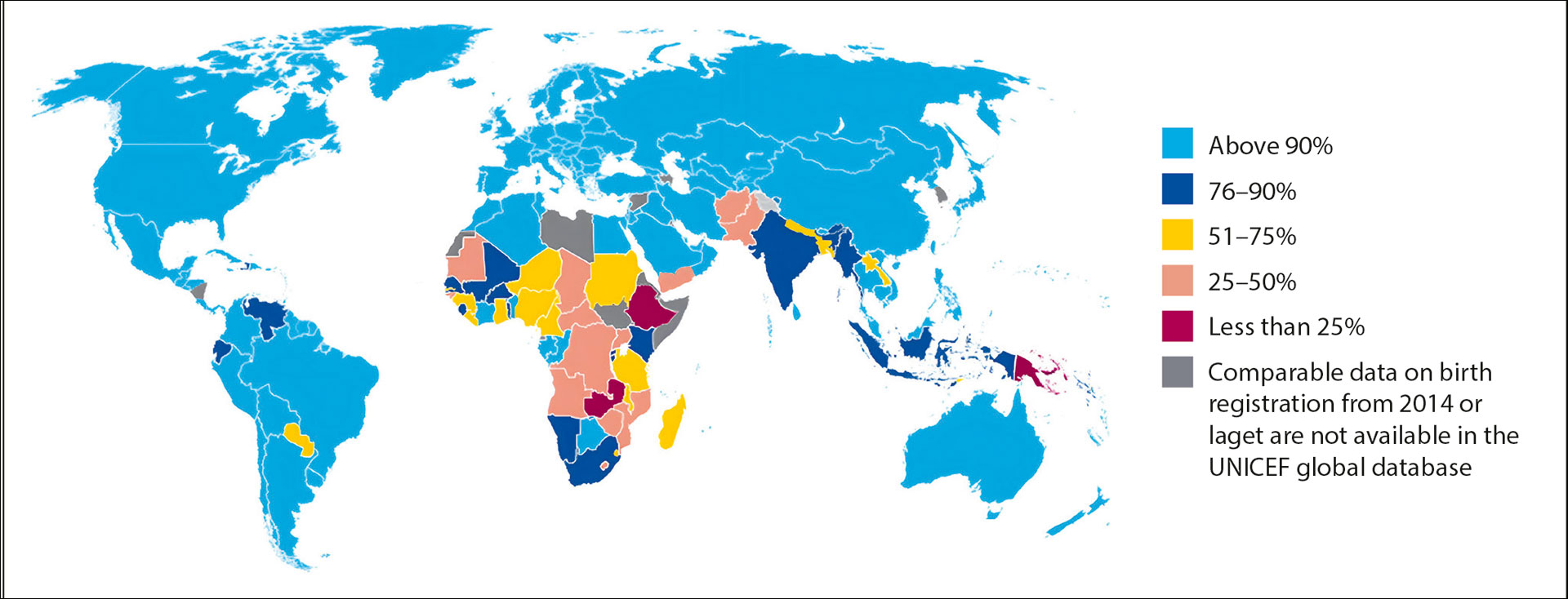

Today, around 1 out of 5, or 150 million children under the age of 5 worldwide are unregistered or lack a birth certificate (figure 1). This essential document serves as proof of registration and is critical for acquiring nationality, and ensuring children can enjoy their rights from birth [2]. In table 1 and figure 2 the percentage of children with birth registration on a global level is illustrated.

More than 8 in 10 unregistered infants live in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia

Figure 1. Number of infants under age 1 whose births are not registered, by region. Source UNICEF 2024 [2].

Figure 2. Percentage of children under age 5 whose births are registered. Source UNICEF 2024 (2).

A rapidly growing child population means that if current trends continue there could be close to 115 million unregistered children under the age of 5 in Sub-Saharan Africa by 2030 [2].

Countries with the lowest level of birth registration are primarily in Sub-Saharan Africa

Many migrants in Europe and the Nordic countries come from Africa and South Asia, stating to be unaccompanied minors, submitting credentials which are questioned. It is therefore evident that the age of migrants is one of the key variables that must be ascertained, since it carries significant legal implications. Many benefits that unaccompanied minors have in asylum processes, are usually inaccessible to adult migrants. Equally, it is important that juveniles are housed under safe conditions, including not with adults stating to be children [4].

Children have different rights from those of adults

Unaccompanied minors constitute a vulnerable group and are legally entitled to protection and special treatment, including the right to a guardian, education and healthcare [2][5]. National legislation determines the acquisition of specific rights and obligations at varying age thresholds [5]. In the Nordic countries, key legal age thresholds include 15 years, which is the age of criminal responsibility and sexual consent, except for sexual consent in Finland and Norway, where it is 16 years. The age of majority is for all Nordic countries 18 years [6][7].

The effect of ethnicity, diseases and nutrition on age analysis

In the past, ethnicity was often considered to play a significant role in medical age assessment [8]. However, more recent studies have challenged this perspective, suggesting that the ethnicity may not significantly impact the dental development or skeletal maturity [9][10][11][12]. The studies that suggest that ethnicity could influence the dental maturity [13], could be subjected to age mimicry, meaning that the differences are more likely to reflect variations in the study populations [14]. Others attribute these differences to variations in socioeconomic factors [15].

Stress and living conditions, as well as systematic diseases, are also believed to impact skeletal and dental development [16][17]. Skeletal age is often delayed in individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, leading to an underestimation of their chronological age [18][19]. A study by Cardoso shows that socioeconomic factors impact skeletal growth more than dental development, indicating that dental development is less influenced by environmental factors [18]. Consequently, individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds maybe assessed as younger than their actual age.

AGFAD

The Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Forensische Altersdiagnostik (AGFAD) is a multidisciplinary working group that brings together forensic pathologists, forensic odontologists, radiologists, and anthropologists. Its primary goal is to harmonize different evidence-based approaches used in medical age estimation and to ensure the quality of the assessments based on available scientific data and expert opinions. AGFAD works to develop and standardize guidelines and methodologies for determining age, particularly in situations where the age of individuals is uncertain, such as in cases involving migrants without valid identification [20].

Ionizing radiation

X-rays, a type of ionising radiation, is useful for diagnostic purposes including assessment of dental and skeletal development. Ionising radiation is a type of energy released by atoms that can be viewed as either electromagnetic waves or photons and can be harmful to humans. However, people are exposed to natural sources of ionising radiation, including background radiation and man-made sources, such as medical radiation [21].

Age assessment in the Nordic countries

Iceland

An agreement between the University of Iceland and Directorate of Immigration (UTL) on age assessment was not renewed as the university believed psychological interviews had not been carried out.

There has been criticism to use of medical age estimation i.e. in the university. It went so far that the university did not authorise age assessment at the Faculty of Odontology. To fulfil social responsibilities, forensic odontologists undertook the assessment on a private basis. An agreement has now been signed between the UTL and National Police Commissioner to host the assessments.

Two forensic odontologists perform age estimation. A panoramic radiograph and intra-oral radiographs of third molars are analysed according to Liversidge [8], Mincer et al. [22], Kullman et al. [23] and AlQahtani et al. [24]. Skeletal age is estimated from hand and wrist according to Greulich and Pyle [25]. The margin of errors is given by averages and SD of each method. The final results are submitted as to whether it is likely that the applicant is younger than 18 years of age. The applicant benefits from any doubt.

Denmark

Medical age estimations are performed by request of the Danish Immigration Service. A physical examination is conducted by a forensic pathologist and includes an interview gathering anamnestic information on general health and upbringing conditions as well as anthropometric measurements of height and weight, and a visual assessment of secondary sexual development based on Tanner stages [26].

Bone age is assessed by a radiologist using a radiograph of the left hand-wrist and the Greulich and Pyle (GP) Atlas method [25]. Dental age is evaluated through panoramic radiographs, complemented by radiographs of all four third molars. The crown and root development of these molars is analyzed by a forensic odontologist using the 10 stages (C½ - Ac) by Gleiser and Hunt, modified by Köhler [27]. Each of the four third molars contribute one stage. Reference studies by Köhler, Haavikko, and Mincer [22][27][28] are used to determine mean chronological ages for each stage.

The final dental age is calculated by averaging the individual dental ages and rounding down to the nearest age. Bone and dental ages are then combined to produce a conclusive age estimate, which includes a most likely age/age range and a margin of error at +/- 1, 2, and 3 standard deviations (SDs), using an SD of +/- 1 year. This approach accounts for an overall range of approximately 8–9 years.

Sweden

To determine if asylum seekers are under or over the age of 18, a medical age assessment is offered by the Swedish Migration Agency, to unaccompanied migrants without credible documents, or uncertainty of age after interviews with social services [29]. The procedure is voluntary and requires written consent from the applicant [30]. Since 2016 the Swedish National Board of Forensic Medicine is commissioned to conduct medical age assessments, both within the asylum process and in criminal proceedings.

The chosen method is based on a validated statistical model that determines the developmental stage of third molar in combination with a skeletal indicator, i.e. MRI of the distal femur [31], radiographs of the hand and wrist [32] or CT scans of the clavicle [33] based on the age threshold being evaluated in relation to the 15-, 18- and 21-year old threshold [34]. Radiographs of the third molar is analysed according to Demirjian [35]. Assessments are presented as probabilities that a person is over or under the age threshold of interest and not as an exact chronological age. Margin of error is always included in the statement [34]. For the staging of third molars, two forensic odontologists assess a panoramic radiograph blinded and independently. If assessments diverge, the lower stage is chosen. The forensic odontologist must have knowledge of age estimation and undergo a calibration exercise, with minimum result of 0.8 (Cohens Kappa). The same requirements are used for assessing skeletal maturity.

Norway

If the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (UDI) is in doubt as to whether an applicant is minor when seeking asylum, the applicant is asked to undergo an age assessment.

Current practice involves only a radiograph of one of the wisdom teeth. Two experienced dentists gauge the developmental stage according to Demirjian’s stages [35]. BioAlder, which is a statistical calculation model based on hand skeleton and lower left wisdom tooth development, yields 75% and 95% prediction intervals for chronological age and based on results from radiographs of the wisdom tooth and hand skeleton [7]. When the application is processed, UDI will always consider the report from BioAlder together with the other details about age.

Finland

According to the Aliens Act [36] the immigration authorities refer asylum seekers to the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) for medical age assessment. In criminal proceedings the police can refer an immigrant to THL for age assessment [37]. The person must give a written consent for the radiographic examinations. The applicant and his legal representatives shall be given information of age assessment, methods used and potential health effects, also information of the consequences of undergoing, and refusing age assessment [37]. The assessment is largely based on dental development and is always performed by two forensic odontologists, one affiliated to THL. They need to have a special competence in forensic odontology, a specialized training program [38]. The examinee is first interviewed including medical history and the measurement of height and weight is performed. Medical forensic age assessment includes a dental panoramic radiograph and a radiograph of the left hand and wrist including BoneXpert analysis (autonomous and validated AI tool, that calculates age) [39].

Age assessment in Europe, EU+ countries

It is recommended to rely on governmental information on age assessment, more than NGOs (nongovernmental organization), often voluntary organizations operating independently of any government, typically one whose purpose is to address a social or political issue and often rely on voluntary donations [40].

No reliable information was obtained from some European countries, therefore only the 30 so-called EU+ countries will be discussed.

European Asylum Support Office (EASO) became in 2022 European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA). It offers practical guidance, key recommendations and tools on the implementation of the best interests of the child. It also brings up-to-date information on the methods conducted by EU+ states [5][41].

12 EU+ countries use a holistic and/or multidisciplinary approach when assessing applicants’ age, 15 not. An age assessment process conducted in another EU+ country are accepted in 9 EU+ countries, not accepted and reassessed in 16 countries [41].

In table 2 all EU + countries, except Ireland, approve some form of medical age assessment. 21 use dental radiographs and 16 dental observations. 23 countries use carpal (hand/wrist) radiographs, 14 collar bone radiographs and 2 knee MRI and 8 sexual maturity observation [5][41].

Advantages of using more than one dental method

Because of the wide variation in material and statistical method, different dental age estimations will give different answers when applied to the same material. It has been recommended to use more than one method, and some believe this would give a more accurate result. With the current knowledge it is more important to look at the background material which constituted the research material and the statistical approach (figure 3).

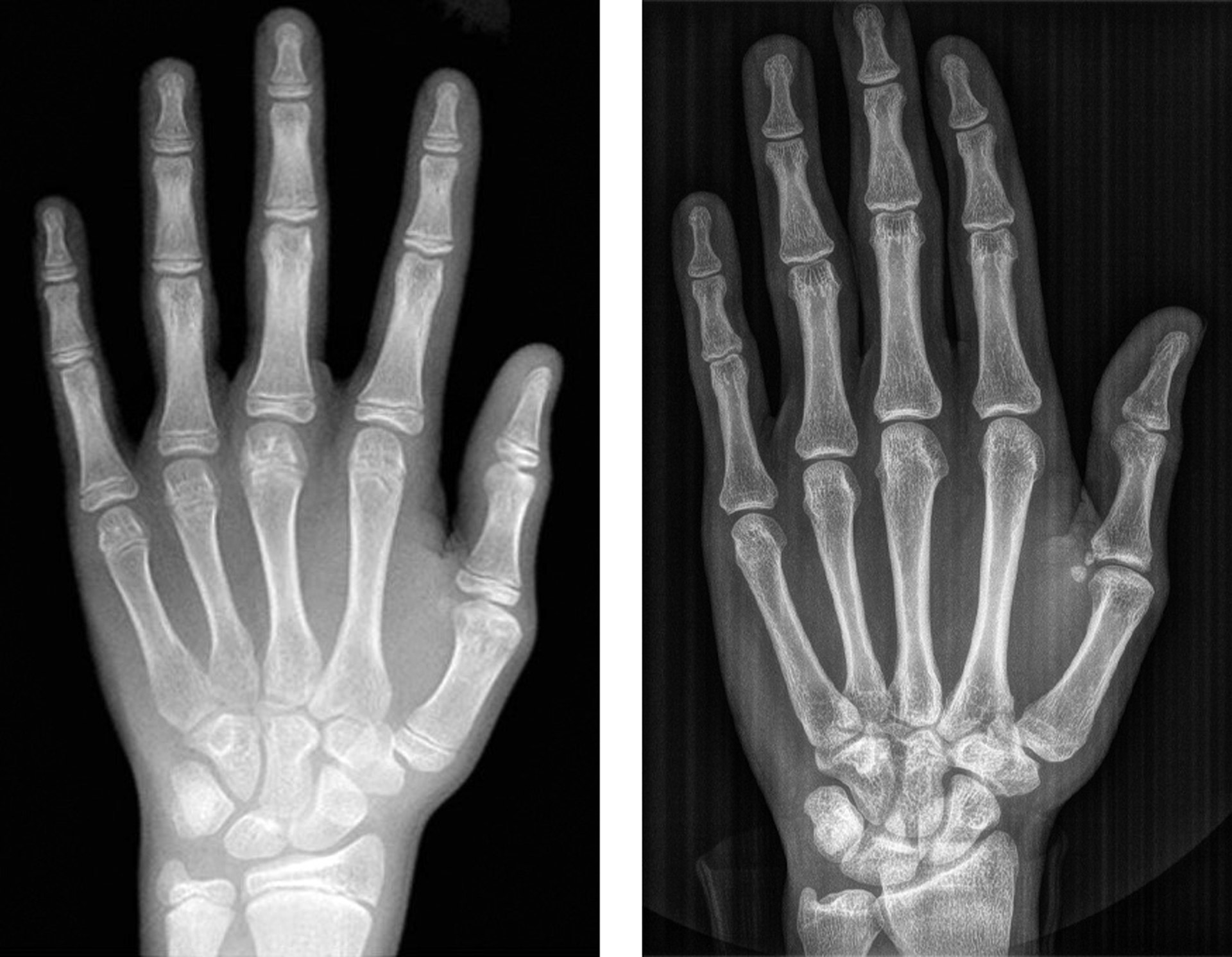

Figure 3. To determine whether an immigrant is a minor or an adult, third molars are useful.

Advantages of using estimation analysis of teeth and bone together

Like dental development is staged, so is bone growth. The most used bones are those in the hand/wrist (figure 4). Like teeth these bones are graded according to an atlas [25]. Teeth and bone develop independently, consequently, it might be a good argument for using both dental and bone development. Research has demonstrated that there is a close correlation between bone and dental age [43]. If bone age and dental age is close it might also be close to chronological age, but if they differ one must look for a reason behind such difference.

Staging whether in bone or teeth is always subjective. BoneXpert is the only automatic and objective grading [39]. Although Norway at present only uses Demirjian’s stages on wisdom teeth the BioAge tables are based on a very large sample from all over the world [7].

Figure 4. According to Greulich and Pyle (25), left: 14 years old boy, right: the epiphyseal lines are obliterated. Male at least 19 years old and female 18.

Presentation of result of age estimation, age range, etc.

All age estimates inherently involve uncertainty, which must be communicated in forensic statements [9]. Ideally, age assessments should be based on multiple biological traits, with the results including a margin of error [42][43]. Some advocate for expressing this uncertainty through a Bayesian or transition analysis approach to reduce the age-mimicry bias [11][44]. The AGFAD propose using the minimum-age as a conservative approach, reducing the unethical risk of erroneously assessing children as adults [6]. However, this can lead to more adults being misclassified as children, potentially compromising the protection of minor´s rights and privileges.

Integrating multiple biological traits into a single age estimate presents significant challenges, including the need for large reference samples and complex computational methods [7][34][44][45]. While Denmark, Iceland and Finland still base the age estimate on reference samples reporting mean ages and standard deviations, Norway and Sweden have successfully developed models that use a Bayesian approach for age assessment. The BioAlder present age estimates as either 75% or 95% probability intervals [7], whereas the Swedish age assessment method reports likelihood ratios, indicating how probable specific developmental stage combinations are for individuals aged e.g. 18 years or older compared to those under 18 years [34].

To reduce inconsistencies in age estimation practices, the Nordic countries should work toward a more unified approach to forensic age estimation in unaccompanied asylum-seeking migrants where the age is questioned.

References

Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 1, 1989 UN General Assembly resolution 44/25. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child.

United Nations Children’s Fund. Birth registration. New York: UNICEF; 2024.

United Nations Children’s Fund. The Right Start in Life: Global levels and trends in birth registration. New York: UNICEF; 2024.

Cummaudo M, Obertova Z, Lynnerup N, Petaros A, de Boer H, Baccino E, et al. Age assessment in unaccompanied minors: assessing uniformity of protocols across Europe. Int J Legal Med. 2024;138(3):983-95.

European Asylum Support Office (EASO). Age assessment practices in EU+ countries: updated findings. EASO Practical Guide Series. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union; 2018.

Larsen ST, Arge S, Lynnerup N. The Danish approach to forensic age estimation in the living: how, how many and what's new? A review of cases performed in 2012. Ann Hum Biol. 2015;42(4):342-7.

Bleka O, Rolseth V, Dahlberg PS, Saade A, Saade M, Bachs L. BioAlder: a tool for assessing chronological age based on two radiological methods. Int J Legal Med. 2019;133(4):1177-89.

Liversidge HM. Timing of human mandibular third molar formation. Ann Hum Biol. 2008;35(3):294-321.

Schmeling A, Reisinger W, Loreck D, Vendura K, Markus W, Geserick G. Effects of ethnicity on skeletal maturation: consequences for forensic age estimations. Int J Legal Med. 2000;113(5):253-8.

Cameriere R, De Luca S, Ferrante L. Study of the ethnicity’s influence on the third molar maturity index (I3M) for estimating age of majority in living juveniles and young adults. Int J Leg Med. 2021;135(5):1945-52.

Thevissen PW, Fieuws S, Willems G. Human dental age estimation using third molar developmental stages: does a Bayesian approach outperform regression models to discriminate between juveniles and adults? Int J Legal Med. 2010;124(1):35-42.

Pechnikova M GD, De Angelis D, de Santis F, Cattaneo C. The "blind age assessment": applicability of Greulich and Pyle, Demirjian and Mincer aging methods to a population of unknown ethnic origin. Radiol Med. 2011;116(7):1105-14.

Olze A, Schmeling A, Taniguchi M, Maeda H, van Niekerk P, Wernecke K-D, et al. Forensic age estimation in living subjects: the ethnic factor in wisdom tooth mineralization. Int J Legal Med. 2004;118(3):170-3.

Rolseth V, Mosdøl A, Dahlberg P, Ding Y, Bleka Ø, Skjerven-Martinsen M, et al. Age assessment by Demirjian's development stages of the third molar: a systematic review. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(5):2311-21.

Schmidt PS, SerrÃo EA, Pearson GA, Riginos C, Rawson PD, Hilbish TJ, et al. Ecological Genetics in the North Atlantic: Environmental Gradients and Adaptation at Specific Loci. Ecology. 2008;89(Suppl 11):S91-107.

Atar M, Körperich EJ. Systemic disorders and their influence on the development of dental hard tissues: A literature review. J Dent. 2010;38(4):296-306.

Adler CP. Disorders of Skeletal Development. In: Bone Diseases. Berlin: Springer; 2000. p. 31-63.

Cardoso HFV. Environmental effects on skeletal versus dental development: Using a documented subadult skeletal sample to test a basic assumption in human osteological research. Am J Phys Anthropol 2006;132(2):223-33.

Schmeling A, Reisinger W, Geserick G, Olze A. Age estimation of unaccompanied minors. Part I. General considerations. Forensic Sci Int. 2006;159(Suppl 1):S61-4.

Schmeling A, Grundmann C, Fuhrmann A, Kaatsch HJ, Knell B, Ramsthaler F, et al. Criteria for age estimation in living individuals. Int J Legal Med. 2008;122(6):457-60.

Abalo KD, Rage E, Leuraud K, Richardson DB, Le Pointe HD, Laurier D, et al. Early life ionizing radiation exposure and cancer risks: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Radiol. 2020;51(1):45-56.

Mincer HH, Harris EF, Berryman HE. The A.B.F.O. study of third molar development and its use as an estimator of chronological age. J Forensic Sci. 1993;38(2):379-90.

Kullman L, Johanson G, Akesson L. Root development of the lower third molar and its relation to chronological age. Swed Dent J. 1992;16(4):161-7.

AlQahtani SJ, Hector MP, Liversidge HM. Brief communication: The London atlas of human tooth development and eruption. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;142(3):481-90.

Greulich WW, Pyle SI. Radiographic atlas of skeletal development of the hand and wrist. 2nd ed. Stanford University Press; 1959.

Tanner JM. Growth at Adolescence. Springfield, IL: C. C. Thomas; 1955.

Köhler S, Schmelzle R, Loitz C, Püschel K. Development of wisdom teeth as a criterion of age determination. Annals of anatomy= Anatomischer Anzeiger: official organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft. 1994;176(4):339-45.

Haavikko K. The formation and the alveolar and clinical eruption of the permanent teeth. An orthopantomographic study. Suomen Hammaslaakariseuran toimituksia= Finska tandlakarsallskapets forhandlingar. 1970;66(3):103-70.

Svensk författningssamling (SFS). 2005:716. Utlänningslag. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/utlanningslag-2005716_sfs-2005-716/

Migrationsverket. Rutin: Informera om medicinsk åldersbedömning, 2025.

Kramer JA, Schmidt S, Jurgens KU, Lentschig M, Schmeling A, Vieth V. Forensic age estimation in living individuals using 3.0 T MRI of the distal femur. Int J Legal Med. 2014;128(3):509-14.

Anderson M. Use of the Greulich-Pyle «Atlas of Skeletal Development of the Hand and Wrist» in a clinical context. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1971;35(3):347-52.

Schmeling A, Schulz R, Reisinger W, Muhler M, Wernecke KD, Geserick G. Studies on the time frame for ossification of the medial clavicular epiphyseal cartilage in conventional radiography. Int J Legal Med. 2004;118(1):5-8.

Heldring N, Rezaie AR, Larsson A, Gahn R, Zilg B, Camilleri S, et al. A probability model for estimating age in young individuals relative to key legal thresholds: 15, 18 or 21-year. Int J Legal Med. 2024;139(1):197-217.

Demirjian A, Goldstein H, Tanner JM. A new system of dental age assessment. Hum Biol. 1973;45(2):211-27.

Aliens Act 301/2004 and the Amendments of the Act up to 389/2023, Finnish Legislation. http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/2004/20040301

Metsaniitty M, Varkkola O, Waltimo-Siren J, Ranta H. Forensic age assessment of asylum seekers in Finland. Int J Legal Med. 2017;131(1):243-50.

Metsänitty M. Age assessment in Finland and dental development in Somali. Helsinki: Department of Forensic Medicine, University of Helsinki; 2019.

Thodberg HH, van Rijn RR, Jenni OG, Martin DD. Automated determination of bone age from hand X-rays at the end of puberty and its applicability for age estimation. Int J Legal Med. 2016;131(3):771-80.

Karns M. Nongovernmental organization. Encyclopaedia Britannica; 2025.

European Asylum Support Office (EASO). Age assessment practices in EU+ countries: updated findings. EASO Practical Guide Series. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union; 2021.

Haugen M, Teigland A, Kvaal SI. Assessing agreement between skeletal and dental age estimation methods. NR-note SAMBA/2/13. Oslo: Norwegian computing centre; 2013.

Sironi E, Vuille J, Morling N, Taroni F. On the Bayesian approach to forensic age estimation of living individuals. Forensic Sci Int. 2017;281:e24-e9.

Tangmose S, Thevissen P, Lynnerup N, Willems G, Boldsen J. Age estimation in the living: Transition analysis on developing third molars. Forensic Sci Int. 2015;257:512.e1-.e7.

Thevissen PW, Alqerban A, Asaumi J, Kahveci F, Kaur J, Kim YK, et al. Human dental age estimation using third molar developmental stages: Accuracy of age predictions not using country specific information. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;201(1-3):106-11.

Corresponding author: Svend Richter, Faculty of Odontology, University of Iceland. E-mail: svend@hi.is

Accepted for publication 14.05.2025. The article is peer reviewed.

Keywords: age assessment, unaccompanied minors, Nordic countries, Europe

The article is cited as: Richter S, Kvaal SI, Gahn R, Metsäniitty M, Larsen ST. Minor or adult? A different approach in the Nordic countries vs Europe. Nor Tannlegeforen Tid. 2026;. doi:10.56373/e69f15bf2e95

Akseptert for publisering 14.05.2025. Artikkelen er fagfellevurdert.

Artikkelen siteres som:

Richter S.Ingeborg Kvaal S.Gahn R.Metsäniitty M.Larsen ST. Minor or adult? A different approach in the Nordic countries vs Europe. Nor Tannlegeforen Tid. 2026;136:24-31. doi:10.56373/e69f15bf2e95