Forensic dental identification

Dental tissues and dental restorations can withstand extreme conditions. For dental identification accurate odontological details recorded on deceased individuals are compared to dental records on missing persons. Forensic dental identification and profiling are common tasks for forensic odontologists. Dental identification can be essential when unknown bodies are found. It may be relevant in single cases as well as following mass disasters, when bodies are decomposed beyond recognition, severely mutilated or skeletal remains exist. Forensic dental identification is recognized internationally as one of three so-called primary identifiers together with fingerprints and DNA.

Clinical relevance

Both ante and post mortem dental data must be available for performing a forensic dental identification. Forensic odontologists depend highly on collaboration with practicing dentists. Without dental data on missing individuals, there is no possibility for comparison with detailed data obtained during an autopsy of a deceased with unknown or uncertain identity. Increased knowledge about the identification processes and the importance of accurate record keeping may encourage interdisciplinary communication and facilitate efficient and well qualified communication between dental practitioners, forensic odontologists and the police when collaboration is needed.

Identifying unknown individuals is essential for resolving criminal investigations, issuing death certificates, ensuring proper burials and providing crucial answers for relatives. Dental identification is an important task in forensic odontology. Ante mortem (before death) dental records are compared with post mortem (after death) findings to verify or exclude identity. Detailed ante mortem (AM) dental records are essential for accurate identification, and in this context encompass all dental information collected during a person’s lifetime. Post mortem (PM) dental data for full documentation of the dental conditions of a deceased are obtained during a meticulous PM forensic dental examination.

The INTERPOL Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) guidelines recognize dental comparison as one of the three primary identification methods, alongside DNA and fingerprints [1].

Teeth are among the most resilient structures in the human body, primarily due to their high mineral content. Enamel is particularly resistant to environmental degradation [2]. Dentin and cementum, while also mineralized, contain a lower percentage of hydroxyapatite and degrade more readily. Dental pulp, being the least resilient part of the tooth, decomposes rapidly after death but remains a valuable source of DNA for forensic identification [3]. Dental restorations, such as amalgam fillings, ceramic crowns, gold restorations, and titanium implants, can withstand extreme temperatures, making them crucial forensic markers [4].

When detailed AM dental records are available dental AM and PM records can be matched quickly. Dental human identification can be vital in mass disasters, such as plane crashes, natural disasters, terrorist attacks, and mass graves, when rapid and accurate victim identification is requested [5][6][7].

PM forensic dental examination

According to DVI guidelines the PM examination related to disasters is carried out by two forensic odontologists (FO’s), one being the examiner of the body, the other recording and verifying the findings [1]. At the PM dental examination (figure 1), a dental status is registered, including tooth status (primary, permanent, or missing), restorations (by surfaces and material), and other dental work such as crowns and implants. Additionally, all information of occlusion, tooth wear and abrasion, tooth position, morphological traits, anatomical anomalies and periodontal condition is gathered [8]. The use of diagnostic fibre light and UV light is recommended. Dental prothesis are described and photographed in situ as well as extra orally and subsequently replaced in situ. Any markings or labelling on dentures are checked and recorded [9][10].

Figur 1

Figure 1. Morgue setting ready for FO dental examination. The deceased will be moved to the autopsy table for examination.

PM-photographs

PM-photographs must document the whole dentition, covering at least five different views: in occlusion, an anterior and both lateral views and an occlusal view of both dental arches [9][10]. A full-face PM image comparison with selfies from the deceased mobile phones can help suggest an identity, subsequently to be verified with primary identification methods [11][12]. Frontal dental images and dental superimposition techniques can similarly assist [13]. PM intraoral surface scans have been introduced as an alternative or supplement to 2D photographs.

PM-radiographs

The radiographic examination (figure 2) should always cover all alveolar bone regions, either with a panoramic radiograph supplemented with separate images of teeth with distinctive features such as root canal fillings or prosthetic restoration, or a full set of periapical images [1]. Impacted teeth, roots, abnormalities and pathologies in bone structure, precise details in the shape of dental restorations, parapulpal pins, screws, implants and other structural features are disclosed by thorough radiological documentation. PM radiographs enable a visual comparison of shapes and positions with AM data. Various conventional radiological methods can be applied. Full computed tomography (CT) scans are often useful for comparison; 3D overviews can be created, and data can be reformatted to simulate periapical and panoramic radiographs.

Figur 2

Figure 2. A handheld cordless X-ray device can be preferable for post mortem intraoral radiographs.

Additional special PM-measures

Dental casts provide a 3D view of the dental arches, tooth morphology and positions, and palatal rugae [14]. When AM casts are available, either conventional impressions are taken to process PM casts, or intra-oral surface scanning is carried out to generate digital 3D images or printed casts. Both methods are extremely applicable for identification purposes [9][10].

Teeth, due to their structure and their protected location in the oral cavity, make them a good source of DNA and may be the only source in special cases. Dental DNA is mainly extracted from cellular cementum and pulp tissue. A molar is most preferable but if not present, premolars have more cellular cementum, whereas canines have a larger pulp cavity. Additionally, roots that are still retained in the socket are protected by the surrounding alveolar bone, reducing the likelihood of contamination [15].

Body conditions

Fresh human remains, after the rigor mortis, as well as decomposed human remains are relatively easily handled for PM dental investigation. However, in highly decomposed and skeletonized human remains teeth may loosen from their sockets and be mingled or lost. In dry, well-ventilated conditions human remains may mummify which makes the skin leathery and mouth opening may thus become difficult, even impossible. With highly incinerated remains teeth become fragile and easily crumble [16]. FOs are trained to perform special tissue sectioning techniques to get sufficient access to the oral cavity even under complex conditions [9][10].

PM age assessment

Particularly in cases where the identity of an unknown individual is unclear, the FO can assist the police by estimating age which helps narrow down possible matches in a DVI incident or in cases of unidentified bodies [9]. For children and subadults, tooth development is one of the most reliable methods for age estimation. Teeth follow predictable developmental stages, and each tooth has a known pattern of formation and development. This process can be assessed through dental radiographs, providing a fairly accurate estimate of the individual’s age [17][18]. In adults the age estimation process becomes more complex, and the assessment is based on regressive changes and degeneration. The techniques for post mortem age estimation in adult teeth include attrition, secondary dentine, periodontal recession, cementum apposition, root resorption, and apical translucency. These methods include tooth extraction (with or without sectioning) or radiographic methods [19]).

Other methods of age estimation is radiocarbon dating (C-14) [20] and amino acid racemization (AAR) [21][22], where C-14 can be used to estimate the date of birth of an individual (incorporation of radiocarbon from the atmosphere in biological tissue) and AAR can be used to estimate the age of biological materials by measuring the conversion of amino acids from their L-from to the D-form.

PM profile of an assumed individual or an unknown individual

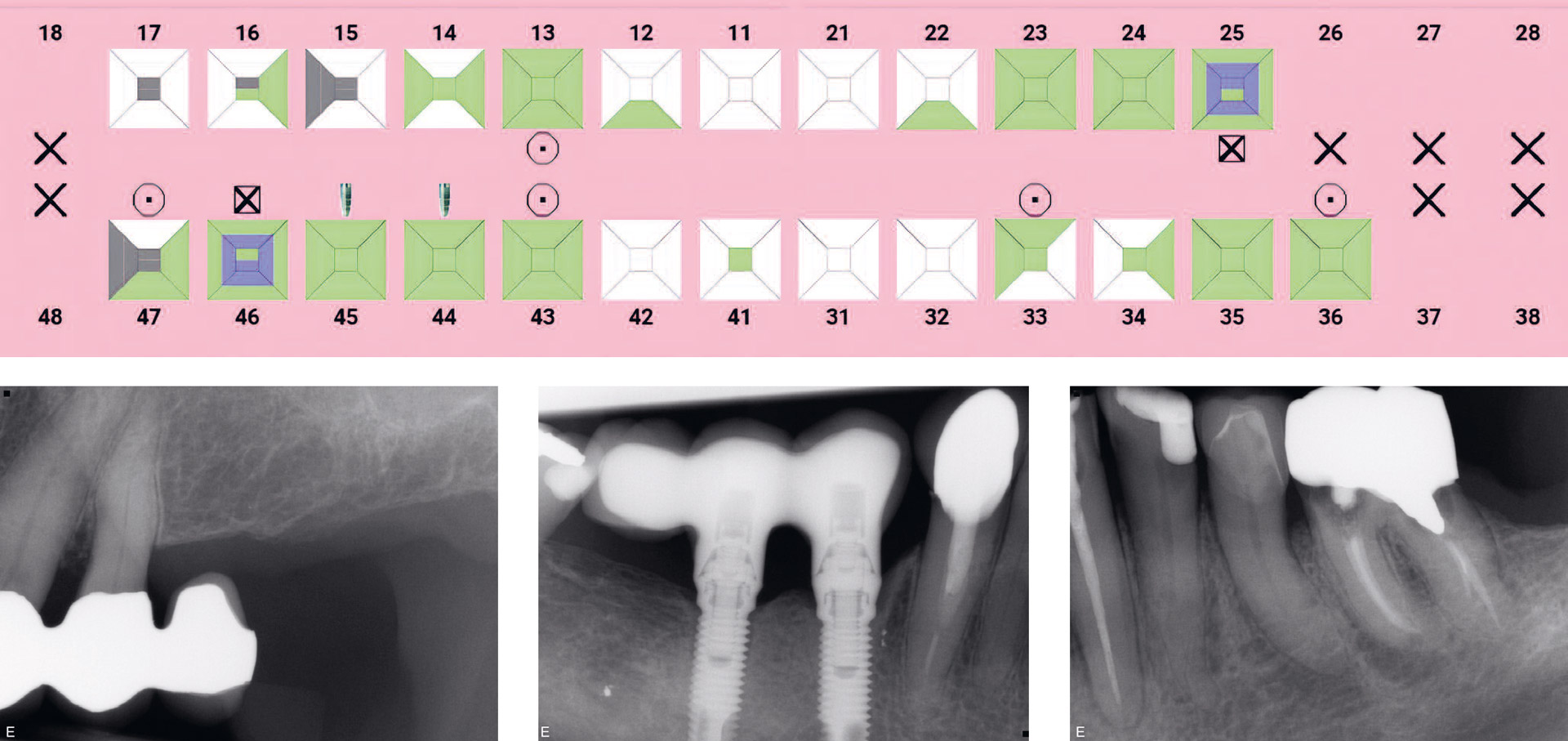

For a PM profile all important dental information (figure 3) gathered in the PM examination is summarized in clear and straightforward writing that can be understood by police and other relevant stakeholders. The dental information is then integrated into the overall description of the unknown body to assist in the identification process. The detailed PM-data of an individual who remains unidentified is subsequently downloaded into internationally recognized software and transferred into a national «Missing persons/unidentified human remains» register. The police may pass the full PM profile, incl. dental, on to e.g. INTERPOL for scrutiny in relation to their international missing persons data base.

Figur 3

Figure 3. PM dental status (3a) and a few selected aspects of intraoral PM radiographs (3b, 3c and 3d).

Collection and handling of AM dental data

The main source of dental AM data is from the dental clinics, but also hospitals, the military and other employers might have clinics or access to dental records. The collection of dental records is done in the Nordic countries by the police and often in close cooperation with FOs. Dental records contain confidential material and must be handled accordingly. Direct transfer of electronic records can be made through encrypted and secure internet systems but may create challenges since the health services and police are generally not on the same systems. Alternatively, electronic records can be copied to appropriate storage media and transported to the FO. It is important that such storage devices are handled with the same care as any other confidential material. Material from abroad may be obtained through INTERPOL or sometimes directly from the DVI-team in that country.

The complete dental records to be collected for identification consist of all available material: the written record, all radiographs, photos, casts, CBCT or CT scans and 3D photo scans. All radiographs should be collected even of poor quality – they might still contain useful information [23]. Electronic radiographs and photos are best collected in digital format. Casts, photos and intraoral 3D surface scans provide extremely important details of the dentition not documented in conventional records [8][9][14]. Occasionally, medical records from a hospital may contain information which are helpful in identifications e.g. following jaw fractures or radiographs of sinuses [24]. Smiling photographs may also assist in the identification [11][12].

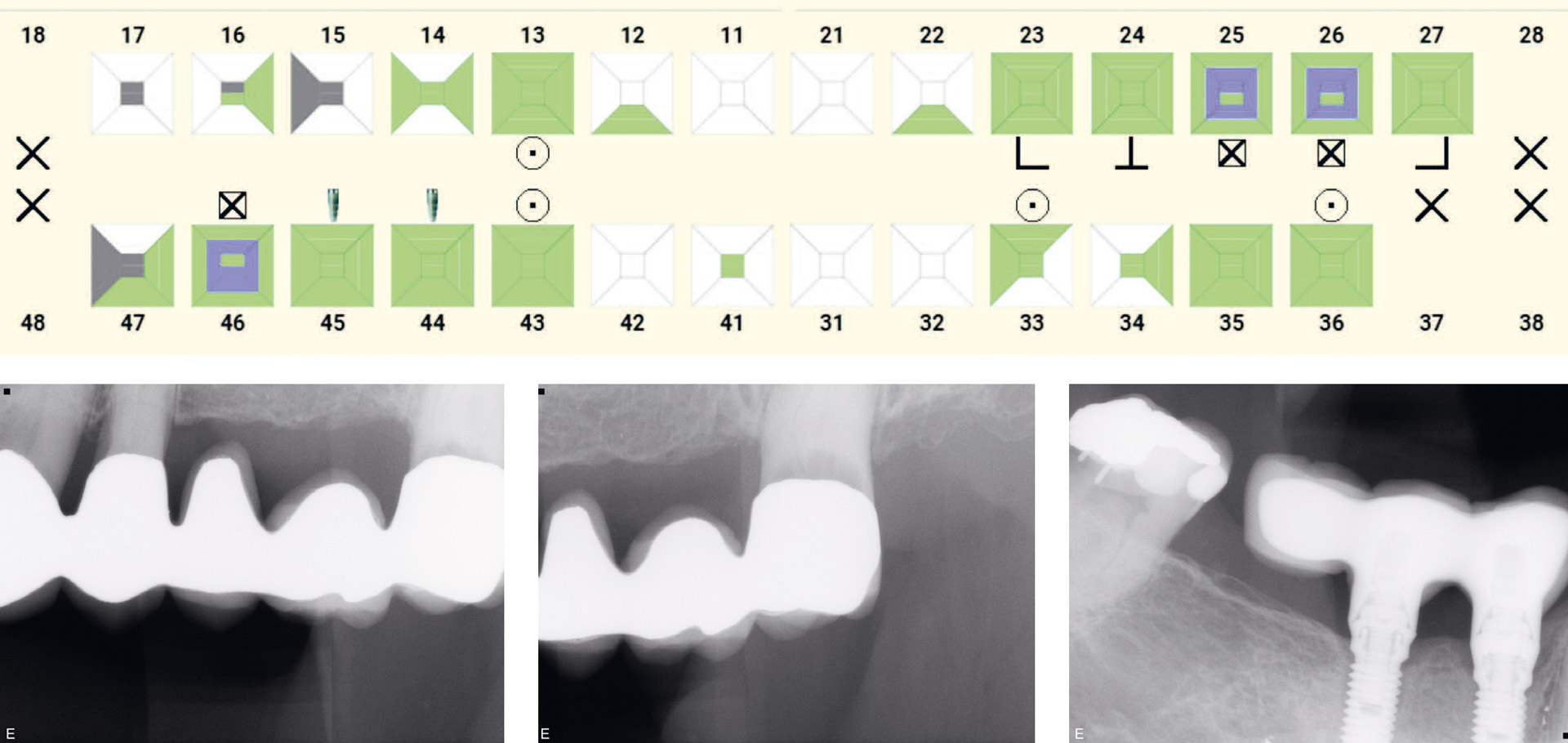

Today, most dental records are electronic, but historic handwritten or typed AM record material is equally important for identification. The FO must interpret and import all AM dental information into a special identification record system (figure 4).

Figur 4

Figure 4. AM dental status (4a) and a few selected aspects of intraoral radiographs (4b, 4c, 4d and 4e) from the AM dental record of the person suspected to be the deceased in PM case shown in figure 3.

Comparison of AM and PM registrations

According to available guidelines quality assessment of both AM and PM data must be performed before the comparison process. To find the best possible matches between AM and PM data sets, it is helpful to prepare a list of special AM and PM markers. This way, only particularly noteworthy features of a missing person or body are recorded in a list. When several deceased individuals need identification a key marker list can be prepared for both the AM and PM subgroups.

The Nordic countries, as well as many other countries worldwide, use the INTERPOL adopted software DVI system (KMD PlassData DVI, Denmark) for recording, documentation and matching in DVI operations [1]it is also applicable for single cases. Special INTERPOL forms are used for digital registration of both AM and PM data which are imported into a structured database. The DVI software can suggest matches, and the FOs must evaluate these matches carefully to depict the most pertinent [25]. These must then be checked by individual comparison of the details in the AM missing persons file with the corresponding findings in the PM file (figure 5). Obviously special findings like prosthesis, implants, root canal fillings, special fillings or rare/striking morphological or anatomical features constitute important proof to the dental identification. However, also a sound inconspicuous dentition without any dental treatment may be identified with certainty when detailed AM dental data are available, e.g. high-quality regular BWs, and intraoral 3D surface scanning prior to orthodontic treatment. When comparing AM and PM data inconsistencies may occur. These may be explainable, i.e. as charting errors or misinterpretations (e.g. were 1st or 2nd premolars extracted o.c.). Incompatible inconsistencies are discrepancies where no explanation is possible, e.g. a restored tooth cannot turn into a sound tooth. The FO must consider all inconsistencies very carefully.

Figur 5

Figure 5a: Comparison of PM and AM dental status (figure 3a and figure 4a).

Figure 5b: Comparison scheme from the DVI software (PM dental codes to the left, AM dental codes to the right) showing discrepancy between the AM and PM dental data (yellow marking). The discrepancy is explainable, a tooth with poor prognosis AM is extracted PM and an adjacent pontic is also removed.

According to international guidelines the FO comparison analysis can result in identification established, rejection (non-identification), or the establishment of a possible or probable identity [1][26]. Insufficient evidence may also be a conclusion [26].

Since no useful data exist on the prevalence of all features that may be recorded in the human dentition no valid objective statistics can be applied to support the FO judgement of the identification level. For the same reason no evidence-based decision criteria based on the number of points of concordance can be established although efforts were made [27][28]). The clinical experience of the involved FOs in combination with thorough scrutiny of all the data by at least two independent FO colleagues result in a comparison report and finally an identification certificate in case identity can be established [2][25].

In DVI operations after mass disasters, an interdisciplinary reconciliation board will review and reconsider all proposed identification reports before a final identification report and certificate can be issued [1][25].

Conclusion

Forensic dental identification is a reliable method for establishing identity and has the advantage of being very fast. However, it relies on the availability of detailed AM dental data, trained forensic odontologists, and required equipment and facilities. In the Nordic countries, a substantial part of the population visits a dentist regularly, therefore AM dental records are commonly available when needed. Due to the rapid expansion of new diagnostic tools in dental clinics (e.g. CBCT-scanners and intraoral surface scanners), the amount of detailed AM dental data is growing and thus available for identification purposes. Forensic dental identification is likely to remain a highly relevant method despite trends towards improved dental health and fewer dental restoration characteristics in younger individuals.

References

INTERPOL Disaster Victim Identification Guide. Lyon: INTERPOL. https://www.interpol.int/How-we-work/Forensics/Disaster-Victim-Identification-DVI.

Wilmers J, Bargmann S. Nature’s design solutions in dental enamel: Uniting high strength and extreme damage resistance. Acta Biomater. 2020;107:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2020.02.019

Schwartz TR, Schwartz EA, Mieszerski L, McNally L, Kobilinsky L. Characterization of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) obtained from teeth subjected to various environmental conditions. J Forensic Sci. 1991;36:979–90.

Alwohaibi RN, Almaimoni RA, Alshrefy AJ, AlMusailet LI, AlHazzaa SA, Menezes RG. Dental implants and forensic identification: A systematic review. J Forensic Leg Med. 2023;96:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2023.102508

Schuller-Götzburg P, Suchanek J. Forensic odontologists successfully identify tsunami victims in Phuket, Thailand. Forensic Sci Int. 2007;171:204–7.

Petju M, Suteerayongprasert A, Thongpud R, Hassiri K. Importance of dental records for victim identification following the Indian Ocean tsunami disaster in Thailand. Public Health. 2007;121:251–7.

De Valck E. Protocols for Dental AM Data Management in Disaster Victim Identification. J Forensic Sci Crim Invest. 2017;4:1–9.

Puri P, Shukla S, Haque I. Developmental dental anomalies and their potential role in establishing identity in post-mortem cases: a review. Medico-Legal. J 2019;87:13–8. doi: 10.1177/0025817218808714.

Xavier T, Alves da Silva R. Dental Identification. In: Brkić H, editor. Textbook of Forensic-odonto-stomatology by IOFOS. Zagreb: Naklada Slap; 2021. p. 35–9.

Berman G, Bush M, Bush P, Freeman A, Loomis P, Miller R. Dental Identification. In: Senn DR, Weems RA, editors. Manual of Forensic Odontology. 5th ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2013. p. 75–129.

Naidu D, Franco A, Mânica S. Exploring the use of selfies in human identification. J Forensic Leg Med. 2022;85:102293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2021.102293

Franco RPA V, Franco A, da Silva RF, Pinto PH V, Alves da Silva RH. Use of non-clinical smile images for human identification: a systematic review. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2022;40:65–73.

Miranda GE, Freitas SG de, Maia LV de A, Melani RFH. An unusual method of forensic human identification: use of selfie photographs. Forensic Sci Int. 2016;263:e14–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.04.028

Jain A, Chowdhary R. Palatal rugae and their role in forensic odontology. J Invest Clin Dent. 2014;5:171–8. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1626.2013.00150.x.

Higgins D, Austin JJ. Teeth as a source of DNA for forensic identification of human remains: A Review. Sci Justice. 2013; 53: 433–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scijus.2013.06.001

de Boer HH, Roberts J, Delabarde T, Mundorff AZ, Blau S. Disaster victim identification operations with fragmented, burnt, or commingled remains: experience-based recommendations. Forensic Sci Res. 2020;5:191–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/20961790.2020.1751385

Ciapparelli L, Clark D. Practical Forensic Odontology. Bristol: John Wright & Sons; 1992. p. 22–42.

Panchbhai A. Dental radiographic indicators, a key to age estimation. Dentomaxillofac Rad. 2011;40:199–212.

Verma M, Verma N, Sharma R, Sharma A. Dental age estimation methods in adult dentitions: An overview. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2019;11:57–63. doi: 10.4103/jfo.jfds_64_19.

Alkass K, Buchholz BA, Druid H, Spalding KL. Analysis of 14C and 13C in teeth provides precise birth dating and clues to geographical origin. Forensic Sci Int. 2011;209:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.12.002.

Helfman PM, Bada JL. Aspartic acid racemization in tooth enamel from living humans. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1975;72:2891–4.

Helfman PM, Bada JL. Aspartic acid racemization in dentine as a measure of ageing. Nature. 1976;262: 279–81.

Sainio P, Syrjänen SM, Komakow S. Positive identification of victims by comparison of ante-mortem and post-mortem dental radiographs. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 1990;8:11–6.

Bianchi IA, Focardi MB, Grifoni R, Raddi S, Rizzo A, Defraia B, et al. Dental identification of unknown bodies through antemortem data taken by non-dental X-rays. Case reports. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2021;39:49–57.

Annexure 6: Phase 4. Reconciliation. In: INTERPOL Disaster Victim Identification Guide. Lyon: INTERPOL 2023. https://www.interpol.int/How-we-work/Forensics/Disaster-Victim-Identification-DVI

NATO Standard AMedP-3.1 Military forensic dental identification. Editon B Version 1 July 2020. Available from: https://www.coemed.org/files/stanags/03_AMEDP/AMedP-3.1_EDB_V1_E_2464.pdf

Keiser-Nielsen S. Dental identification: certainty V probability. Forensic Sci. 1977;9:87–97.

Keiser-Nielsen S. Person identification by means of the teeth: a practical guide. Bristol: Wright; 1980. p. 1–132.

List of abbreviations

AM Ante mortem / before death

PM Post mortem / after death

INTERPOL International Criminal Police Organization

DVI Disaster Victim Identification

FO Forensic Odontologist

Corresponding author: Rebecca Gahn. E-mail: Rebecca.gahn@rmv.se

2025-05-12

The article is peer reviewed.

Keywords: Forensic dentistry, Identification, Disaster victims, DVI

The article is cited as: Bindslev DA, Gahn R, Hurnanen J, Jonsdottir SR, Kvaal SI. Forensic dental identification. Nor Tannlegeforen Tid. 2026; 136:

Akseptert for publisering 12.05.2025. Artikkelen er fagfellevurdert.

Artikkelen siteres som:

Bindslev DA, Gahn R, Hurnanen J, Jonsdottir SR, Kvaal SI. Forensic dental identification. Nor Tannlegeforen Tid. year;vintage. doi:10.56373/6966309577b0a